Ejzenštejn - The Image Revolution

The Uffizi is hosting an exhibition entitled "Ejzenštejn. The Image Revolution" to commemorate the first centenary of the Socialist Revolution in Russia through the drawings of one of the 20th century's greatest cultural revolutionaries.

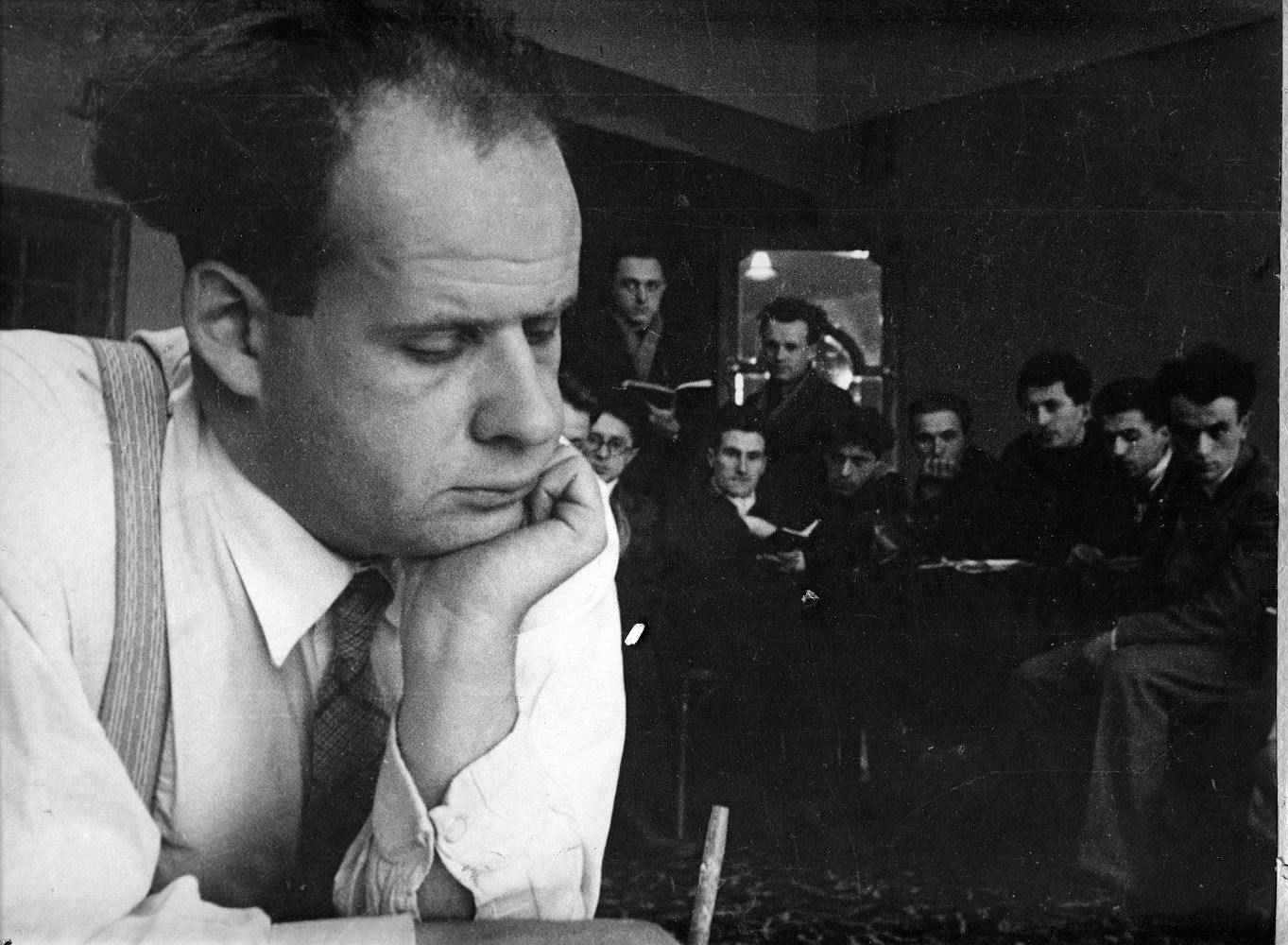

The multi-faceted career of film director, theoretician and tireless draughtsman Sergei. M. Ejzenštejn (Riga, 1898 – Moscow, 1948) was to the world of images what the uprising of 1917 was to the social, political and economic organisation of the Russian Empire (and elsewhere), but with the additional ability to last over time, inspiring generations of artists.

The exhibition explores the many facets of Ejzenštejn's talent ranging from his activity as a draughtsman to his work as a film director, discovering a common thread in the inspiration they both sought in Italian late medieval and Renaissance art.

The seventy-two drawings, all from the Russian State Archive of Literature and Arts (RGALI), have been stringently selected on the basis of two principles. The first is the independence of the drawings, almost all of which Ejzenštejn produced between the early 1930s and 1948, considering them a kind of automatic transcription of his thought capable of setting down on paper the constant flow of ideas that both inspired and dialogued with his films yet without being subordinate to them in any way. The second is an extension of the first and concerns the style of the drawings marked by a tight, linear technique that echoes the 14th and 15th centuries, whilst also fully partaking of the artistic climate of his day with its echoes of Surrealism and of Neo-Expressionist distortions.

Thanks to these drawings that are pure silhouette, the exhibition also offers the visitor a unique insight into Ejzenštejn's concept of editing, firstly on account of the way his figuration tends to unravel and to re-form on the basis of "cuts" that hint at a constant renewal of meaning, but also, indeed above all, on account of the value of drawing which should be appreciated in its deployment of sequences on the basis of strips that may truly be called "cinematic", inasmuch as they are arranged in a close series as through they were ideal stills in dialogue with the director's films projected on the walls of the rooms in the Sale di Levante della Galleria delle Statue e delle Pitture.

Eike D. Schmidt, the director of the Gallerie degli Uffizi, writes: "The technique of drawing based on pure outline naturally harks back to that technique's heyday, the Neo-classical era, coinciding with the philosophical school of German idealism and thus also with that of Hegel, which Ejzenštejn adapted after arriving in Mexico. In fact one of the Parcae drawings alludes to the style of certain Pre-Columbian bas-reliefs, while other drawings echo Cézanne's female nudes, especially the bathers on the river banks in his landscapes. Yet the primary aesthetic model for the Parcae dancing and stretching so expressively leaps out at the observer unequivocally: it is Henri Matisse's Dance (1910), which is now in the Hermitage in St. Petersburg but which Ejzenštejn undoubtedly admired and studied in the State Museum of Modern Western Art in Moscow where it was moved from the home of Sergei Shchukin following the Great Revolution".

Ejzenštejn's cinematographic material has also been arranged in the exhibition in such a way as to conduct a thought-provoking dialogue both with the art of the past and with his approach to editing. On the one hand, the screenings mix details and scenes from Strike, Battleship Potemkin, Alexander Nevsky and Ejzenštejn's other film masterpieces with certain details from Leonardo da Vinci's Adoration of the Magi and Last Supper and from Paolo Uccello's Battle of San Romano, revealing significant similarities; while on the other, the films build a journey that visually recounts Ejzenštejn's editing, in a "crescendo" leading from the rapid, individual shots in the first room via the frames in the second to the complete sequences in the third and fourth. The fifth room marks the apogee of the director's life and career, his final drawings combining and contrasting with the ironic, everyday images of Ejzenštejn the man taken from a series of archive videos specially selected and assembled for the occasion.

Thus this image revolution, bringing the seventh art (as Ejzenštejn called the cinema) to the Uffizi for the first time, has a face that is at once old and new in constant interaction. And the Renaissance, in addition to being an outstanding storehouse of images, also becomes the synonym par excellence of the cultural rebirth for which every revolution should aim in its endeavour to become permanent.

In the climate of rebirth and revolution fostered by the exhibition at the Uffizi, Florence and Bologna have joined together to launch a Revolution Week (7–10 November 2017), a cycle of events kicking off with the exhibition in Florence and continuing with an international conference entitled Avant-garde and Revolution. The Cinema of Sergei M. Ejzenštejn, organised by the Cineteca di Bologna in conjunction with the Gallerie degli Uffizi (Bologna, 8 November), and winding up with a second international conference promoted by the Kunsthistorisches Institut in Florenz – Max-Planck-Institut: The future is our only goal. Revolutions of Time, Space and Image. Russia 1917 – 1937 (Florence, 9-10 novembre).

Those who knew Sergei Ejzenštejn personally tell us that he often said how sad he was never to have been able to set foot in the Uffizi. This exhibition offers us the opportunity to right one of History's minor wrongs.

The exhibition is curated – and the catalogue, published by Giunti, is edited – by Marzia Faietti, Pierluca Nardoni and Eike D. Schmidt and promoted by the Ministero dei beni e delle attività culturali e del turismo with the Gallerie degli Uffizi, the Fondazione Cineteca di Bologna, the Russian State Archive of Literature and Arts (RGALI), the Pushkin State Museum of Fine Arts and Firenze Musei.