Pietro Aretino and the Art of the Renaissance

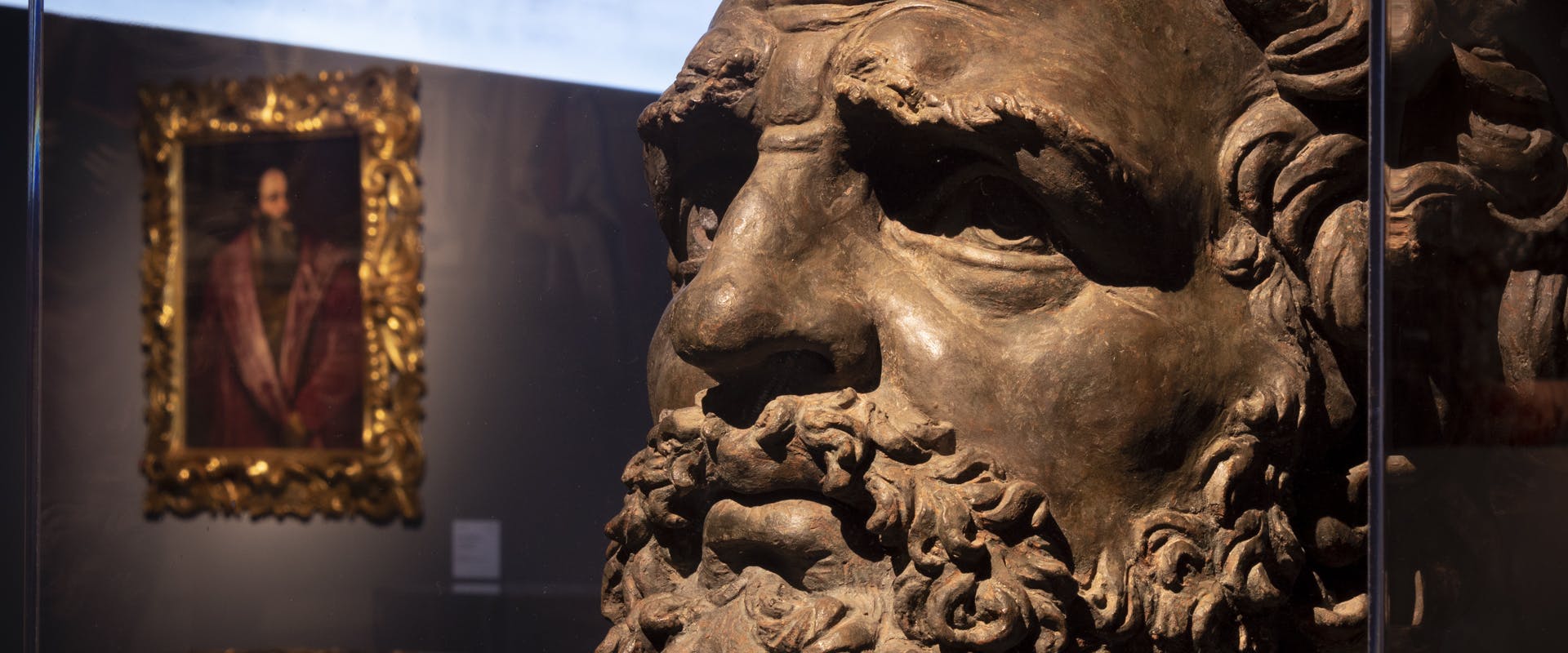

Roughly a hundred paintings, sculptures, examples of the applied arts, tapestries, miniatures and printed books reconstruct the world of Pietro Aretino (1492–1556), a great thinker of the 16th century

“Men say that I am the son of a courtesan; I am not unhappy with that; but I have the spirit of a king. I live free, I enjoy myself, and thus I may count myself a happy man."

Pietro Aretino

Poet, playwright, scathing wit, counsellor to the mighty and a talent scout of great artists, Pietro Aretino (Arezzo, 1492 – Venice, 1556) is known today chiefly for his celebrated, and scandalous, Sonnets of Lust. Yet he was in fact one of the most authoritative cultural voices of the 16th century, a thinker of whom the secular and religious powers alike stood in fear, a friend to the mercenary captain Giovanni dalle Bande Nere, to Cardinal Giulio de' Medici who brought him to the court of Pope Leo X in Rome, and to such masters as Titian, Raphael and Parmigianino who portrayed him in their works and with whom he corresponded enthusiastically and at great length.

To the multi-faceted figure of Aretino, a pioneer (as Giorgio Vasari himself admitted) in the field of art history and criticism as an independent discipline, the Uffizi is now, for the very first time, devoting a major exhibition, showcasing important loans from international museums. The exhibition comprises over 100 exhibits ranging from painting and graphic art to printed works, sculpture and the decorative arts, recounting Aretino's life and spirit in the places that symbolise the Renaissance where he lived and wielded his immense influence on the dynamic cultural world in the first half of the 16th century: Rome under the Medici Popes, Mantua with the Gonzaga family, Venice and Doge Andrea Gritti, Florence at the time of Dukes Alessandro and Cosimo I, but also Urbino, Perugia, Arezzo and Milan.

The exhibition also includes a film "cameo". In an effort to highlight the deep bond of friendship linking Aretino to Giovanni dalle Bande Nere, visitors will be able to watch segments of "The Profession of Arms", the film that Ermanno Olmi devoted to the figure of the great Medici mercenary captain, in which Aretino, played by Sasa Vulicevic, is not just the offscreen narrator but also appears in many scenes.

"Pietro Aretino and the Art of the Renaissance" is part of the extensive series of events organised by the Gallerie degli Uffizi and the City of Florence in 2019 to celebrate the 500th anniversary of Cosimo I's birth, but at the same time it offers us a foretaste of the celebrations for Raphael Year due to kick off in a few months' time..

The exhibition is curated by Anna Bisceglia, Matteo Ceriana and Paolo Procaccioli.

A Brief Biography

Pietro Aretino was born in Arezzo in 1492. After training in letters and painting in Perugia and Siena, he joined merchant and banker Agostino Chigi's entourage to worm his way into Roman society under the Medici Pope Leo X. These were the years when Aretino used his stinging wit to lend his voice to the 'speaking' statue known as Pasquino, in a unique combination of prophetism and all-round political satire.

After spending time in the Po valley, between the camp of Giovanni dalle Bande Nere and Federico II Gonzaga's court in Mantua in the early 1520s, Aretino moved to Venice where he was to spend the rest of his life. He was doubtless encouraged to make that choice, in part at least, by the rocambolesque affair of the Sonnets of Lust and the ensuing rift with the court of Pope Clement VII, the dramatic outcome of which was an attempt on his life on 28 July 1525.

After the Sack of Rome in 1527, by which time he had already settled in Venice, he succeeded in integrating to perfection in a political and propaganda system in which he cooperated with Titian and Sansovino on Doge Andrea Gritti's ambitious urban renewal programme. But then his intuition of the potential offered by the Venetian printing industry radically changed his astonishing career as a man of letters, which was characterised at this juncture by a direct relationship with the world of the figurative arts, in the role of accredited mediator between workshop and patron. Thus in the 1530s, thanks to an alliance with publisher Francesco Marcolini, Aretino managed to forge a profile for himself as "the world's secretarius", praised and feared on every front by the humble and the mighty alike. His matchlessly incisive command of the vulgar tongue extended to embrace all of the literary genres that he practised simultaneously and with consummate ease, publishing in rapid succession his comedies (the Cortigiana was published in 1534), his pornographic dialogues (Ragionamento and Dialogo were published between 1534 and 1536), his Letters (the first book was published in 1538) and his paraphrases of the Bible and hagiographic revisitations (published between 1534 and 1543).

He settled stably in the imperial orbit in 1536, receiving a stipend from Charles V and cultivating a complex patronage rapport with Alfonso d'Avalos, the Governor of Milan. But it was in 1539, when Pietro Bembo was made a cardinal in the new climate of Paul III Farnese's pontificate, that Aretino added a new piece to the construction of his persona by, for many years, fuelling the dream of also one day being raised to the purple and thus of joining the ranks of the papal court. Yet while not totally groundless, his hopes were to be dashed in the early 1550s at the very moment in which his virtual fellow countryman Cardinal Del Monte's election to the papacy as Julius III appeared to hold such promise. Death took him without warning in Venice on 21 October 1556, leaving behind it a trail of infamy that even succeeded, over time, in suggesting that he had died from laughing too much. In 1559, under Pope Paul IV Carafa, his entire literary output was officially banned, although it continued to enjoy clandestine circulation under the pseudonym Partenio Etiro. It has taken centuries to banish a black aura that recent scholarship alone has managed to dispel, restoring one of the leading figures of the Italian Renaissance to the place he so eminently deserves.