The Japanese Renaissance. Nature on painted screens from the 15th to the 17th centuries

The splendour of Japanese artistic culture and its close relationship with nature: 39 amazing painted screens on view. Among these characteristic expressions of Japanese art, on display also some artworks revealed for the first time

One-of-a-kind in Europe, a new large exhibition on Japanese art has just been inaugurated at the Uffizi. It covers a period which correspondingly runs from the early Italian Renaissance until the early 1600s, and consists of folding screens and sliding doors, many of which - praised as National Treasures and Noteworthy Cultural Heritage at home - come from museums, temples and the Agency for Cultural Affairs of Japan. The artworks, all on paper and extremely delicate, will be displayed in three rotations of 13 pieces a time in order to preserve their integrity.

This is certainly a worthy opportunity to celebrate 150 years of diplomatic relations between Italy and Japan, which date back to the Treaty of Amity and Commerce of 25th August 1866. "So Italy and Japan meet at the Uffizi to renovate their amity - says the Italian Minister of Cultural Heritage Dario Franceschini - and culture turns out to be a bridge between two great countries, both rooted into ancient and amazing civilizations respectively".

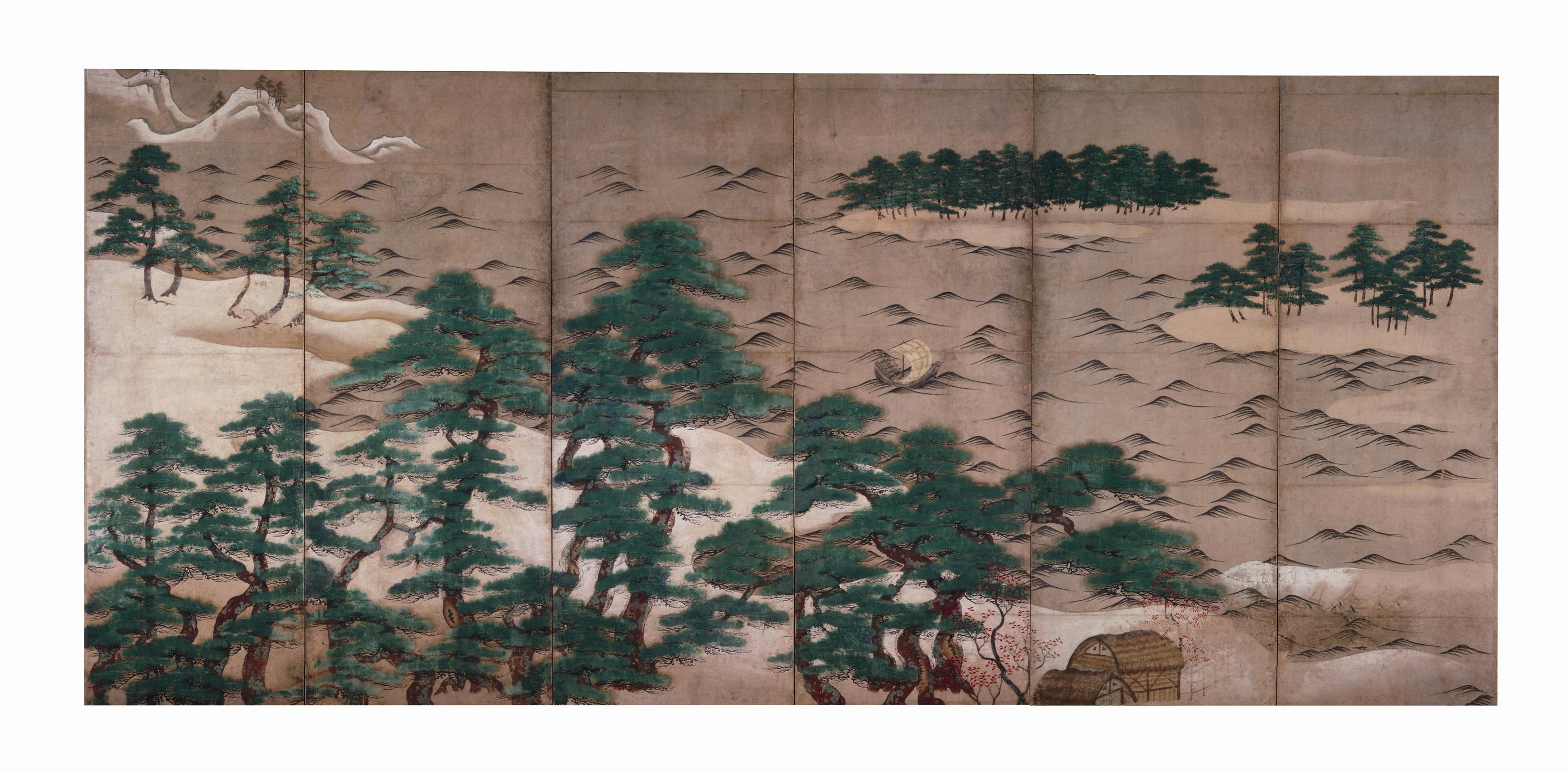

The exhibit gathers a wide selection of 39 large paintings of landscapes and nature. Many of them are generally not on view, even in Japan. They are characteristic folding screens (byōbu) and sliding doors (fusumae), typical of the Golden Age of Japanese art between the Muromachi period and the early Edo period (15th – 17th centuries), when two opposite aesthetic criteria arose for the first time and tackled one another apparently surviving until the present day.

On the one side, in fact, is a monochrome and evoking painting consisting of empty spaces interrupted only by thin and swift lines indebted to Zen philosophy and Chinese culture. It is thus not surprising that this kind of stern art have been highly praised by the warrior class whose members loved to decorate temples and samurai's abodes that way already from the Kamakura period (1185–1333).

On the other side is a more traditional Japanese kind of painting, with gold grounds and unvarying coloured backgrounds against which delicate natural elements stand out. More immediate and communicative, such a painting was rather used to embellish aristocratic and bourgeois abodes, castles and palaces. On display, landscapes characterized by rarefied and symbolic ambiances executed by masters like Hasegawa Tōhaku, Kaihō Yūshō, Unkoku Tōgan. They drew inspiration from the traditional Kanō painting featuring flowers and birds, the four seasons, or places made famous by literature and poetry, generally depicted with brilliant colours in perfect yamatoe style.

Expressing gratitude for the creation's beauties, these joyful ambiances as well as the stern Zen characters alluding to austerity, poverty, imperfection, irregularity of forms and materials express a conception of nature as a mirror of human soul, which had already been known throughout centuries with the phrase mono no aware, namely, “affection for things”: a precious teaching and a cause for reflection for Western culture too; an opportunity to reconsider the environment and the relationship of man with it.

Painted on one or rather two imposing screens with two or six folds, or decorated on the sliding doors' panels which used to separate rooms, these artworks express the beauty and fickleness of the universe surrounding us as well as the close relationship of Japanese people with nature. Man becomes part of it by plunging into landscapes with that pantheistic attitude typical of the Shintoists, which is at the heart of all the literary and figurative culture of Japan.

As the Commissioner for Cultural Affairs of Japan Mr. Miyata Ryōhei says «this exhibition offers Italian visitors the opportunity to admire the splendour of Japanese artistic culture and also to realize its deep sensitivity towards nature».