An esoteric Seventeenth-Century masterpiece arrives at the Uffizi: the Witch by the ‘cursed’ painter Salvator Rosa

The imposing canvas, just acquired by the museum, will become a highlight in the Gallery within the 17th Century painting rooms

A sulphurous masterpiece of esoteric art, The Witch by the tormented and original 17th-century painter Salvator Rosa, becomes part of the Uffizi collection. Soon it will be welcomed in the Gallery, in the rooms of the 17th-century masters.

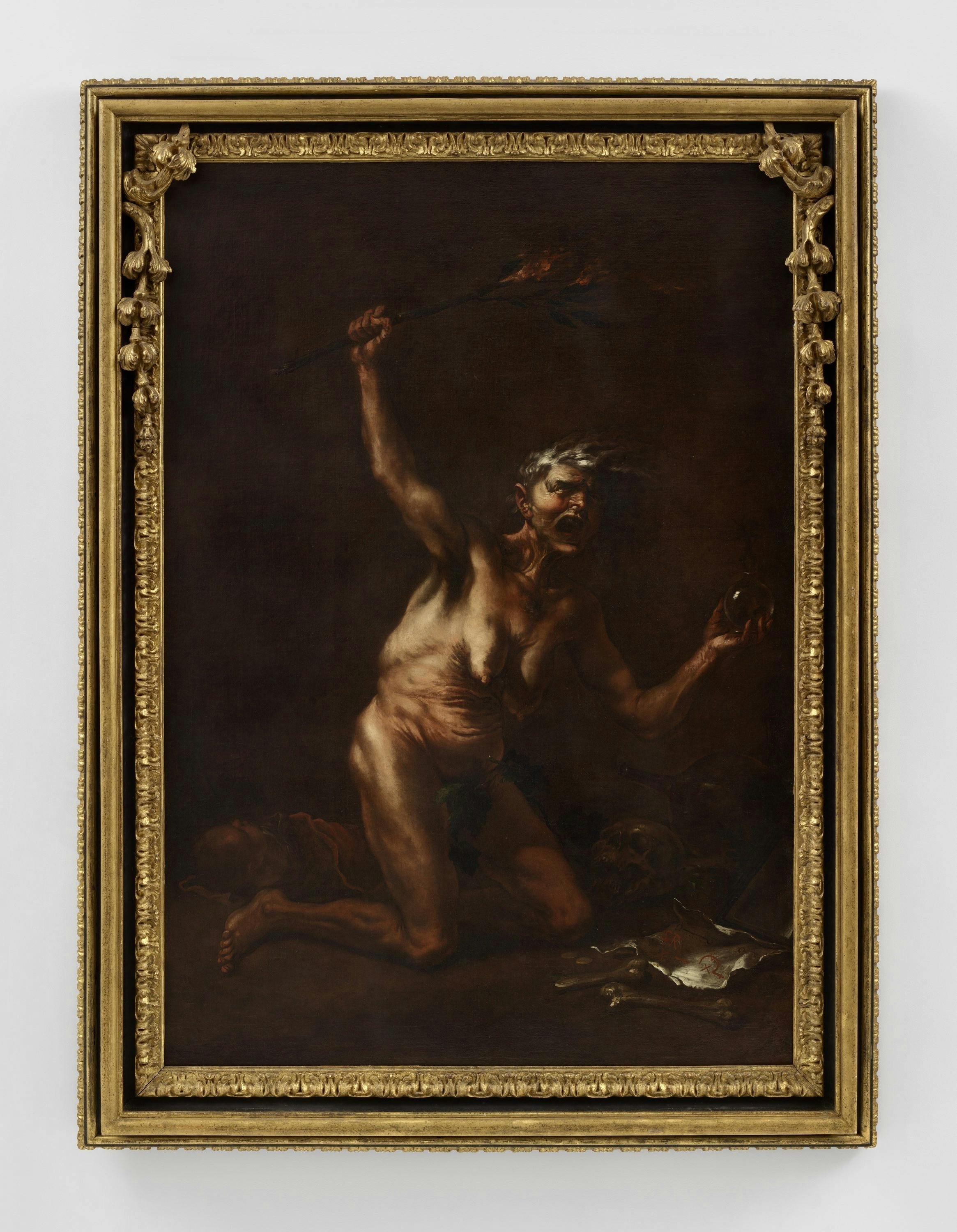

In the centre of the imposing painting, the wicked sorceress appears kneeling; her body is ungainly and sagging, and the painter almost obsessively accentuates the signs of ageing, blending feminine features with more androgynous characteristics. The face is twisted; the old woman stares with eyes filled with anger, curses, and wields a burning branch in her left hand, while showcasing in the other a spherical container from which emerges a devilish figure, symbolising the infernal forces summoned by her evil magic. Scattered on the ground are various objects, each of which bears an obscure meaning within the context of the macabre event: a glass jug, some coins, a mirror, pieces of bones, a skull, and in the foreground, standing out against the dark background, a white sheet bearing esoteric symbols along with the unmistakable monogram of the author, ‘SR’. The most sinister and gruesome detail of the composition, however, is the child wrapped in a cloth, in the dim light in the background, behind the witch. The child is dead: a reference to the legend that witches used children's blood to prepare their magic potions.

The witchcraft subject recurs in the production of Salvator Rosa and typically belongs to the years of his Florentine residence, during which this canvas should also be chronologically located. Indeed, from 1640, Rosa was salaried by Cardinal Giovan Carlo de’ Medici and remained so until 1648. The attendance at the Medici court, along with the highly refined environment of the Florentine academies and scholars—who were strongly interested in esoteric, philosophical, and hermetic themes and engaged in the study of ancient philosophical texts, such as the Corpus Hermeticum (which arrived in Florence in the latter half of the fifteenth century, translated by Marsilio Ficino and first published in 1470)—decisively influenced Rosa's choices towards the necromantic representations of this period, including 'Witches and Spells' (now in the National Gallery, London), the 'Witch’ of the Capitoline Museums (depicted in a meditative attitude, unlike that of the Uffizi), and the 'Falsehood' and the 'Temptations of St. Anthony,' both housed in the Palatine Gallery of the Pitti Palace. The Witch displays a similar dense and stained quality as these paintings, coupled with a focus on grotesque details, extended to the improbable and the deformed. In the iconographic choice, Rosa recalls the

tradition of the Nordic painters of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, from Dürer to Baldung Grien to Jacques de Gheyn. The painter also dedicated some literary compositions to the theme of magic, including an ode entitled The Witch (1646), focusing on the curse cast by a witch against a man who did not reciprocate her love, a text that also contains many elements in common with the painting recently acquired by the Florentine museum. The museum paid about €450,000, and its scientific committee gave a favourable opinion on the purchase; the work had been abroad for a sufficient number of years so that it could no longer be subject to restrictions, and, being an object of interest for several international museums, it risked never returning to Italy.

Simone Verde, Director of Uffizi Galleries: "The valuable acquisition of Salvator Rosa's Witch into the collection allows us to qualitatively enhance the core of the museum's seventeenth-century painting collection with an artist who, Neapolitan by birth and training, moved between Rome and Florence, uniquely characterising Italian and European art of the mid-century.' The Uffizi Galleries boast a substantial number of paintings by Rosa, mostly landscapes and genre scenes, but - apart from the Temptations of Saint Anthony - the magical and witchcraft theme, developed by the painter precisely in Florence, had been absent until now; thanks to the arrival of The Witch, we can say we have filled this gap more than satisfactorily. With this masterpiece, an authentic theoretical manifesto of Baroque painting, the Uffizi are therefore endowed with another powerful icon, returning to Italy a masterpiece otherwise destined for exile".

Biographical notes on Salvator Rosa, "cursed" artist

Salvator Rosa (1615–1673) is one of the most original artists of the seventeenth century. Known for his impetuous temperament and his lack of regard for patrons, he was one of the first examples of a 'tormented artist'. In his lifetime, he achieved international fame, which lasted until the nineteenth century, especially among art collectors of the British aristocracy. Rosa is renowned primarily for his wild landscapes, with broken trees and rocky ravines, often populated by bandits, landscapes that influenced the painters of

the sublime of the 18th and 19th centuries. The romantic image of his life will be propagated by Lady Morgan in her fictionalised biography The Life and Times of Salvator Rosa (1824), but the artist himself contributed to such fame, asserting: “I do not paint to accumulate wealth but solely for my own satisfaction; it is necessary to let myself be carried away by the impulses of enthusiasm and to wield the brushes only when I feel compelled by it.” Born in Naples in 1615, Rosa moved to Rome in 1635, where he became famous as a painter of landscapes and battle scenes; but he imprudently antagonized his contemporaries, including the sculptor Bernini. This may have prompted him, in 1640, to accept the invitation of Giovanni Carlo de’ Medici to move to Florence, where he prospered as a poet, philosopher, and painter in the circle of virtuosi cultivated by the cardinal. His house became the reference point of a cultured society, the Accademia dei Percossi. During the Florentine sojourn, Rosa executed a series of profoundly poetic single figures, which are today among his most beloved paintings: Philosophy (London, The National Gallery), Poetry (Hartford, Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art), Self-portrait (New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art), and Self-portrait as Pascariello (in a private collection). The intensity of these works expresses his personal synthesis between painting and poetry. In 1649, Rosa left the Medici court to return to Rome, where he continued to be an impetuous and controversial figure for the rest of his life. In 1651 he painted Democritus in Meditation (Copenhagen, Statens Museum for Kunst), a masterpiece that encapsulates his concern for the vanity of human endeavours. He developed a classicizing style, which earned him an invitation to paint for Louis XIV; an invitation he refused. He remained in Rome until his death in 1673. On his deathbed, Rosa married Lucrezia Paolini, who had been his lover and model for 30 years.

Salvator Rosa

Napoli, 22 luglio 1615 – Roma, 15 marzo 1673

La Strega

1647 - 1650 circa

Olio su tela

212 x 147 cm

La Strega

Poesia di Salvator Rosa

Era la notte, e l’orme

a le prede d’amor quieta movea

turba di Citherea,

turba che mai non dorme,

perché nell’aria bruna

scintillar non vedea

sotto povero ciel luce di luna.

Infra quest’ombra amica

movea Filli le piante,

implacabil nemica

d’amator non curante,

e rassembrava al moto, alla favella,

agitando la face

d’uno sdegno tenace,

dell’Inferno d’amor furia novella.

Poiché l’amar non vale,

dicea colma di rabbia,

a meritar d’un traditor la fede,

girerò questo piede,

aprirò queste labbia,

scoppierò dall’interno

di vietati scongiuri arte fatale,

potente a convocar nume d’Averno.

Nume che vendichi

l’ira di lui,

nume che l’agiti

nei regni bui,

nume che fulmini

l’empio mal nato, ond’io tradita fui:

poiché il crudel non m’ode,

poiché non prezza il pianto,

alla frode, alla frode,

all’onte, all’onte,

all’incanto, a l’incanto,

e chi non mosse il ciel, mova Acheronte.

Io vo’ magici modi

tentar, profane note,

herbe diverse, e nodi,

ciò ch’arrestar può le celesti rote,mago circolo,

onde gelide,

pesci varij,

acque chimiche,

neri balsami,

miste polveri,

pietre mistiche,

serpi, e nottole,

sangui putridi,

molli viscere,

secche mummie,

ossa, e vermini,

suffumigij,

ch’anneriscano,

voci horribili,

che spaventino,

linfe torbide,

ch’avvelenino,

stille fetide,

che corrompino,

ch’offuschino,

che gelino,

che guastino,

ch’ancidano,

che vincano

l’onde stigie.

In quest’atra caverna,

ove non giunse mai raggio di sole,

da le tartaree scuole

trarrò la turba inferna,

farò ch’un nero spirto

arda un cipresso, un mirto,

e mentre a poco, a poco

vi struggerò l’imago sua di cera,

farò che a ignoto foco

sua viva imago pera,

e quand’arde la finta arda la vera.

Forse così questa beltà schernita

con magica possanza

estinguerà per me l’empio che ha vita,

ravviverà per me morta speranza.

Poiché il crudel non m’ode,

poiché non prezza il pianto,

alla frode, alla frode,

all’onte, all’onte,

all’incanto, all’incanto,

e chi non mosse il ciel, mova Acheronte.