The Demidov Collection in the Uffizi Library

The Uffizi Galleries have preserved 37 volumes from the dispersed library of Villa Demidov in San Donato, Florence. These works arrived at the Department of Prints and Drawings and in the historical library of the Uffizi between 1970 and 1975, after the auction of the furnishings of Villa Demidov in Pratolino, which was arranged by the last heir of the family, Paolo Karageorgevič, in 1969.

According to Cesare da Prato, the library of Villa San Donato was described as 'magnificent'. At the time of Pavel Pavlovič, nephew and heir of Anatolij, it used to collect up to 40,000 volumes. Pavel Pavlovič chose to house the library in the captivating and unusual setting of the ancient medieval church of San Donato in Polverosa, which had been acquired by his uncle Anatolij because it bordered the villa. The library's subjects ranged from fine arts to geography and history, up to economics and travel literature, thus reflecting the diverse interests of Anatolij and Pavel Pavlovič Demidov. However, the reconstruction of its exact content appears to be a really daunting task, as the library was dispersed in numerous directions: from the unknown destinations of the buyers of 6,900 volumes, mainly in French, sold at auction in 1880 at the behest of Pavel Pavlovič; to the volumes in Russian, along with maps and atlases, transported to Nizhny Tagil in the Urals, where the Demidov's mines were located; and finally to the donations of volumes owned by the family to various libraries following the wishes of the Demidov heir, Paolo Karageorgevič, after the auction organised in Pratolino in 1969.

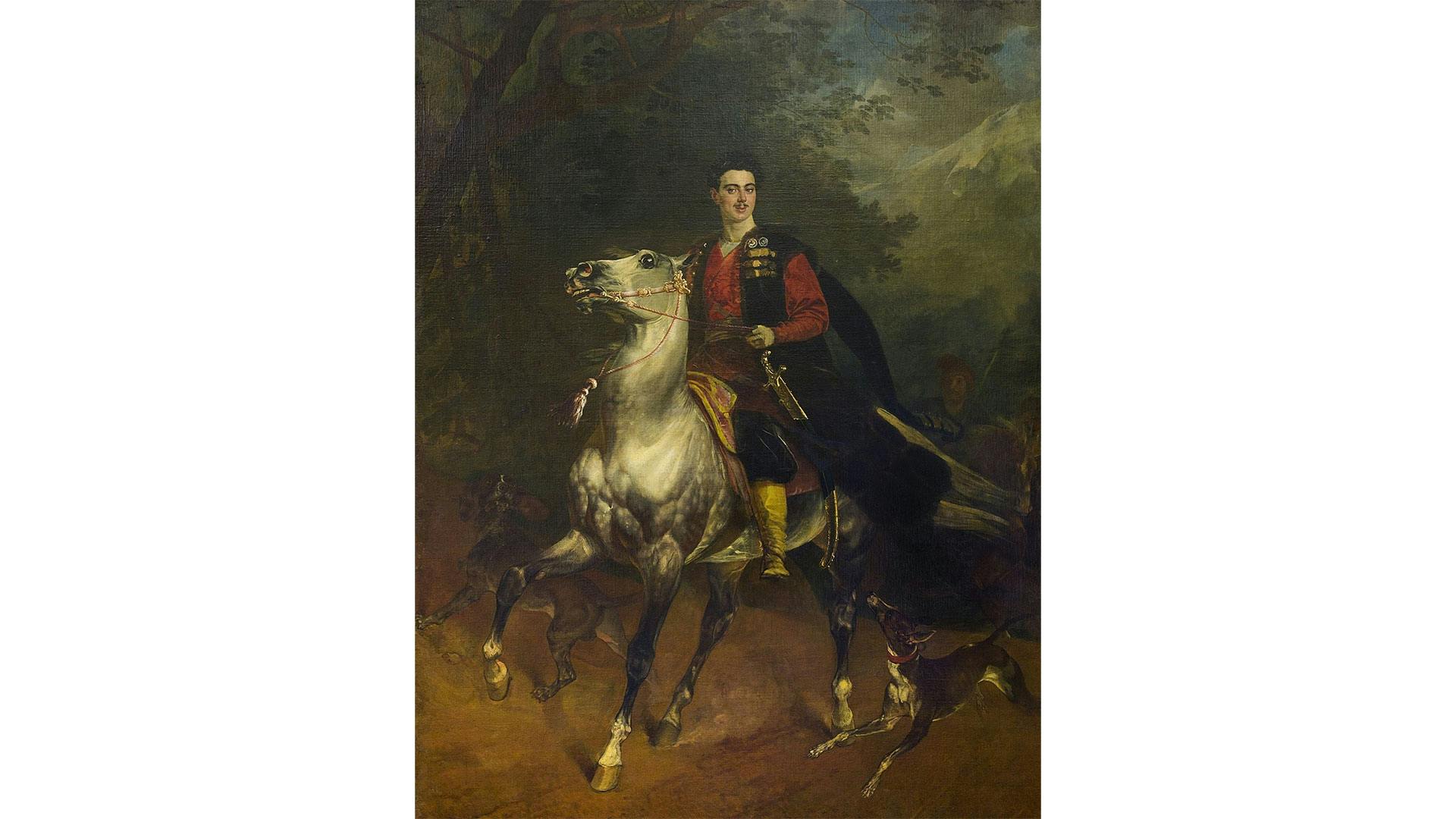

In the 19th century, under the Grand Duke rule, the city of Florence was accustomed to the comforts and elegance displayed by the gentlemen of the 'Grand Tour', but it had never witnessed the opulence and grandeur exhibited by the Demidov family. Their fabulous wealth stemmed from the exploitation of copper, silver, manganese and malachite mines in Siberia, as well as from extensive business and trade networks all across Europe. Anatolij (1813-1870), one of the two sons of Nikolaj Demidov (1774-1828), was the figure most closely related to Florence. He decided to settle there in 1824 to benefit from the mild climate that would alleviate his health issues. Anatolij, with his exuberant temperament and sometimes theatrical demeanour, was a cultured and curious collector, as well as an indefatigable traveller. Even though he was born in Russia, he preferred to spend his time in Paris and other European cities. In Florence, he used to reside in Villa San Donato, which his father was just starting to build in their estate of San Donato in Polverosa, on the road to Prato just outside the city.

Charity initiatives

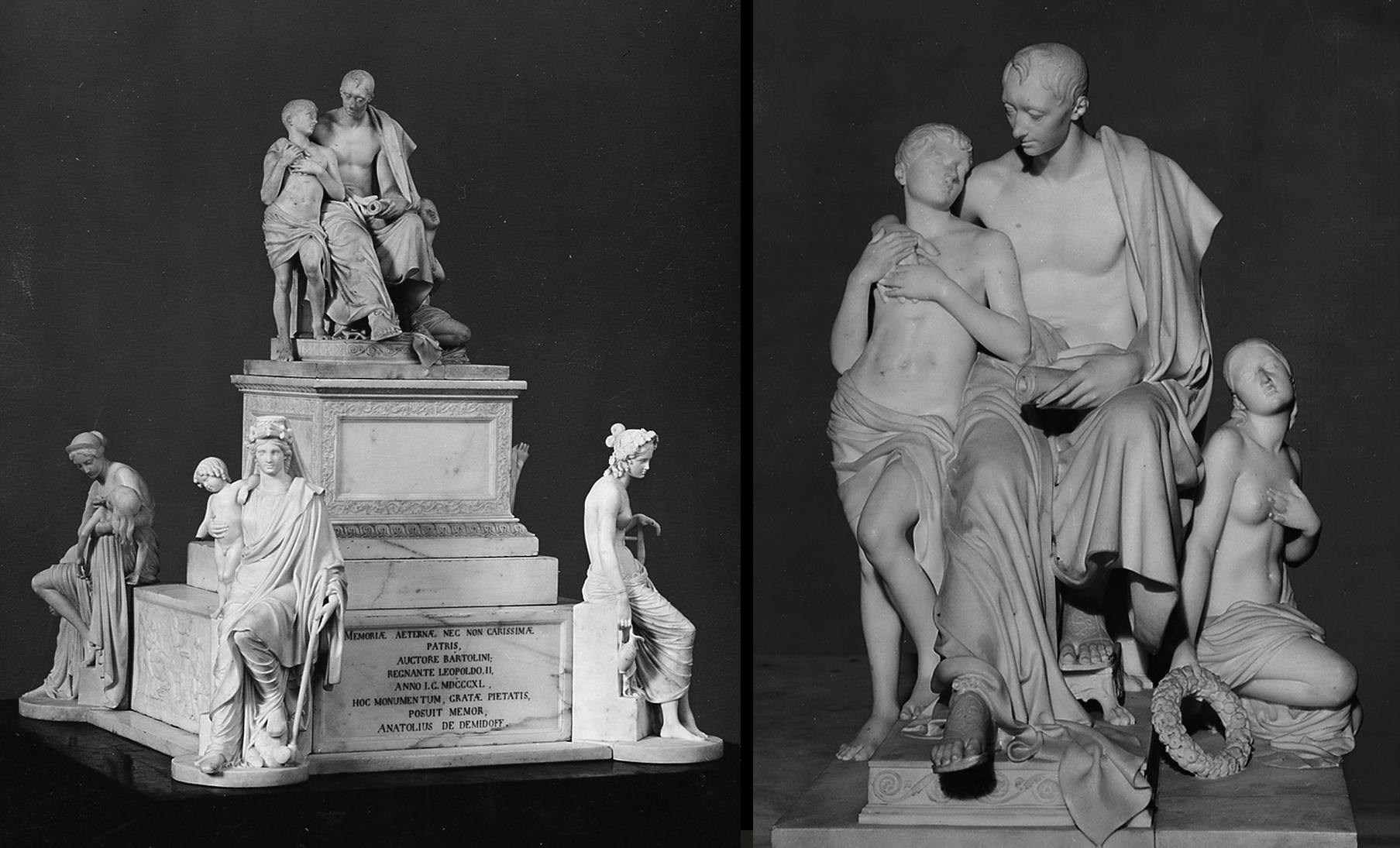

Following Nikolaj's death in 1828, Anatolij, alongside his brother Pavel Demidov (1798-1840), kept financing his father's initiatives, although embracing a broader and more magnificent approach. In particular, he poured his resources into charitable endeavours in Tuscany, including the promotion of the silk industry, the establishment of institutions for the welfare and education of the underprivileged, and the pioneering construction of railways. The Demidov family's motto, 'Acta non verba' (Facts not words), actually epitomised their commitment to action over mere rhetoric. In Florence, Anatolij continued to support the boys' school in the neighbourhood of San Niccolò, which had been originally founded by his father in 1828 next to their opulent residence at Palazzo Serristori. His contribution enhanced the school's facilities, providing a new pharmacy and ensuring a regular salary for a surgeon who guaranteed free medical care to the young students. The Uffizi Library houses the volume Des Pieuses Institutions Démidoff à Florence. Histoire et réglement, dedicated to the 'Maison de Bienfaisance Démidoff', an institution for impoverished girls founded by Anatolij Demidov in St. Petersburg in 1833. This insightful text, authored by the school's director, Marquis Carlo Torrigiani, outlined the structure of the San Niccolò school in Florence, which employed a system of mutual teaching where older students, the so-called 'monitori', mentored the younger ones. In recognition of his philanthropic endeavours and to strengthen the bond between Florence and the Demidov family, Grand Duke Leopold II of Habsburg-Lorraine bestowed upon Anatolij the title of 'Count' in 1836, followed by the prestigious title of 'Prince of San Donato' in 1840. This latter honour coincided with Anatolij's marriage to Princess Matilde Bonaparte, daughter of Jérôme Bonaparte, the former King of Westphalia and Napoleon's younger brother.

The princely residence

The construction of the building complex, greenhouses and gardens known as Villa San Donato started shortly before the death of Nikolaj Demidov (1774-1828), who commissioned architect Giovan Battista Silvestri with the project. After Nikolaj's passing, Pavel Demidov (1798-1840), the eldest son, wanted Silvestri to continue the work. Completed in 1831, the villa was designed in neoclassical style and stood as a unique addition to Florence. It actually bore resemblance to the Venetian villas with lush gardens and noble palaces built in St. Petersburg, such as the Tauride Palace. The villa sat uninhabited for a few years after Pavel was summoned back to Russia for military service and later to work as a governor. Meanwhile, Anatolij (1813-1870), who was only fifteen when his father died, concluded his studies in Paris. It wasn't until 1835 that Anatolij arrived in Florence. There, he envisioned transforming Villa San Donato into a hub for silk production in Tuscany, an endeavour he generously supported. In 1840, Anatolij married Princess Matilde Bonaparte in the chapel of the villa. For the occasion, Grand Duke Leopold II of Habsburg-Lorraine granted Anatolij the title of 'Prince of San Donato'. Since then, Anatolij started to decorate the objects and furnishings purchased for San Donato with the coded monogram 'AD' - his initials intertwined and surmounted by a crown - and turned the villa into a bustling hub of social life, hosting balls, receptions and visits from esteemed guests. Unfortunately, the marriage with Matilde lasted only a few years, as Anatolij parted ways with the princess in 1846. Nevertheless, the transformation of Villa San Donato continued even further. Anatolij enlisted prominent architects like Luigi Del Moro, Giuseppe Martelli and Niccolò Matas to significantly enlarge the main building. Inside, he showcased artworks and treasures acquired with relentless zeal, mainly from Paris, welcoming local artists to stay to update on the latest international art trends. In the external area, Anatolij enhanced the villa with magnificent greenhouses with rare plants and a zoo featuring exotic animals, as well as with stables and indoor riding arenas for horses, another great passion of his.

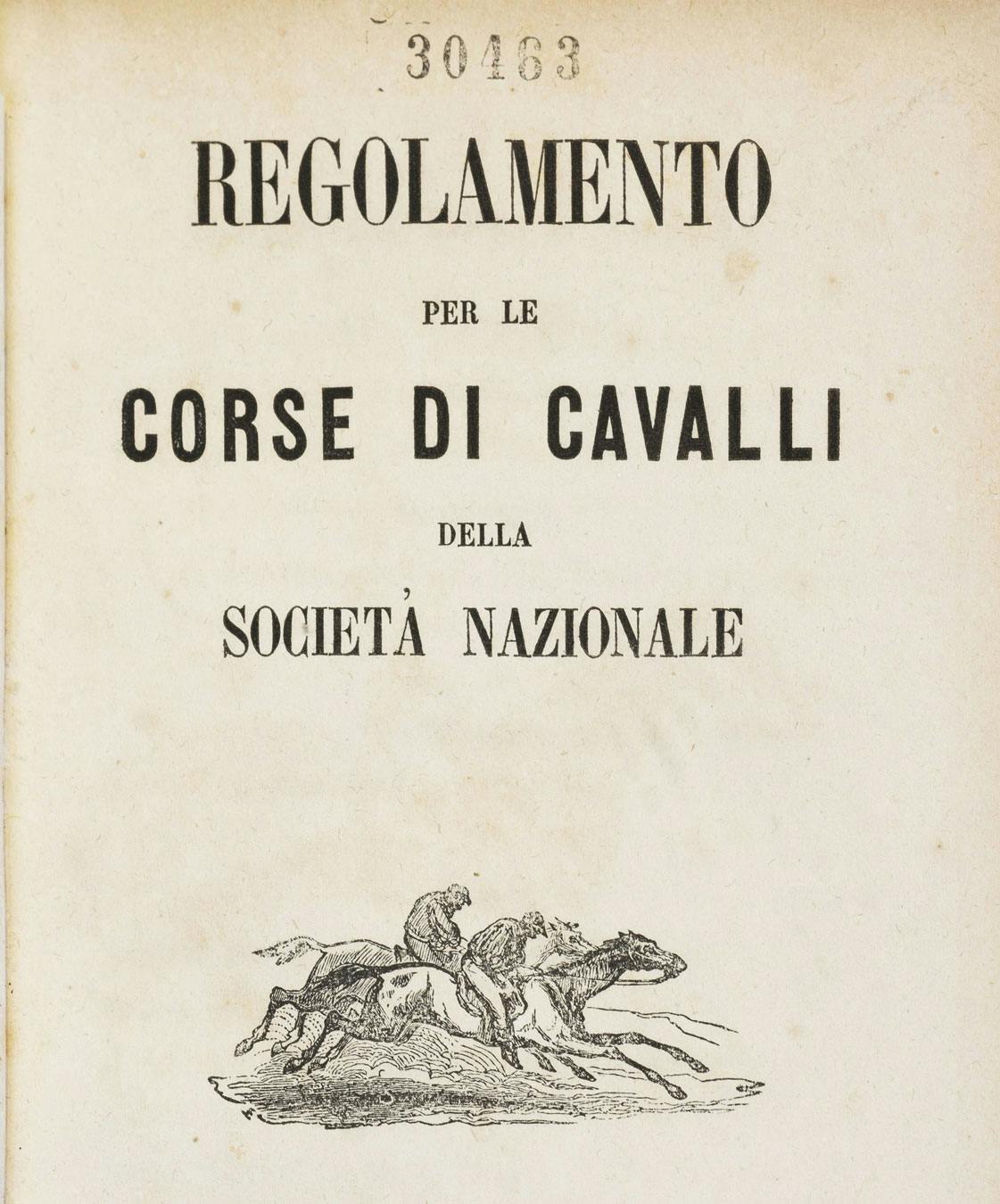

Rules of horse racing

A testament to this passion is the booklet on the Rules of Horse Racing published in Turin by the Société Nationale in 1853. It belonged to the 'Bibliothèque de San Donato' and bears the metallic coat of arms of the Demidov family at the centre of the front cover. The emblem is surmounted by a crown and adorned with stylised drawings of mining tools, the source of the family's immense wealth. The coat of arms appears together with the motto "Facts not words", written in Russian (Delami ne slovami), which alludes to the charitable activities traditionally promoted by the family. The volume features a handwritten interleaf added to the list of members, on which the name 'Demidoff, Principe Anatolio' is written in pen, thus suggesting the personal use of this booklet by the Prince of San Donato. The list of members includes, among others, Camillo Benso Count of Cavour and his brother Giacomo. Anatolij was certainly one of the prominent figures in social events like horse races, which at the time were attended by the most important members of high society, such as the two Counts Cavour.

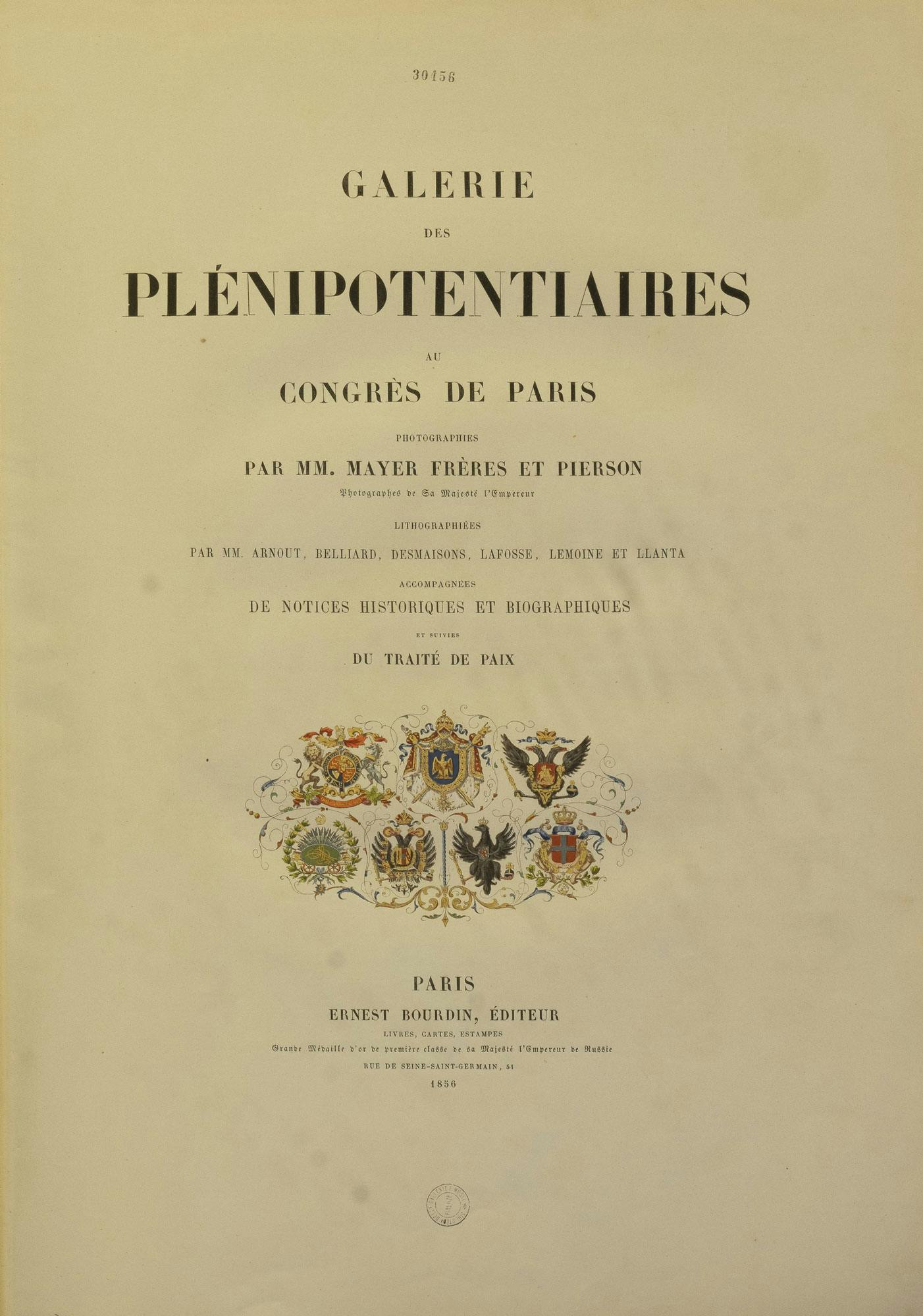

Cultural initiatives and the 'Galerie des plénipotentiares'

In 1837, Anatolij Demidov (1813-1870) embarked on a journey to Crimea, accompanied by a large retinue of scientific advisors and artists, with the aim of studying the optimal utilisation of the region's economic and mining resources, documenting its landscape, and portraying the customs and traditions of its inhabitants. Notably among them was the artist Auguste Raffet, who was renowned for his ability to swiftly capture live scenes and always accompanied Anatolij on these endeavours. Anatolij Demidov documented the results of the Crimean expedition in his work Voyage dans la Russie Méridionale et la Crimée par la Hongrie la Valachie et la Moldavie, which was published between 1840 and 1842 by the Paris publisher Bourdin and translated into Italian, Russian, English and German. He intended to dedicate the work to Tsar Nicholas I Romanov, whom, however, did not appreciate the dedication. Nicholas I, an autocrat and staunch defender of tradition, frowned upon a Russian-born individual like Anatolij, who despite the immense wealth preferred to reside abroad without serving at court or in the army, as was customary for Russian feudal aristocracy. For the same reason, Tsar Nicholas I refused to recognise Anatolij's title of 'Prince of San Donato', which had been conferred upon him by the Grand Duke of Tuscany. Approximately twenty years later, the same publisher of Voyage dans la Russie Méridionale et la Crimée - Bourdin of Paris - presented to 'Son Altesse, Monseigneur, le Prince Anatole de Demidoff' the album La Galerie des plénipotentiaires as a 'hommage respecteux'. The album featured photographic portraits and reproductions of signatures of the delegates to the Congress of Paris in 1856, including that of Camillo Benso, Count of Cavour, who represented the Kingdom of Sardinia. The Congress of Paris in 1856 approved the peace treaty that restored geopolitical balance among the Russian Empire, the European powers, and the Ottoman Empire after the devastating Crimean War (1854-1856), which caused immense human losses, both military and civilian. During that war, Anatolij Demidov was not a mere bystander, as he actively collaborated with the Red Cross to organise prisoner exchanges and provided clothing and food supplies at his own expense to Russian prisoners of war in England.

Initiatives in memory of Napoleon Bonaparte

After his separation from Princess Matilde Bonaparte in 1846, Anatolij Demidov (1813-1870) devoted himself with even greater dedication and passion to the buying and selling of artworks at Parisian or London auctions. This activity provided him with emotions akin to those experienced by stock market players, leading him to constantly change and expand his art collections until they filled every space of his palace in Paris and Villa San Donato in Florence. Among the art objects he collected, a special series consisted of Napoleonic relics, which he acquired in large quantities from the Bonaparte family and other relatives who were in exile in Florence. In 1851, Anatolij even managed to purchase Villa San Martino, where Napoleon Bonaparte used to reside during his exile on the Island of Elba, and commissioned architect Niccolò Matas to build the grand Napoleon Museum beneath the villa, which was completed in 1856, to display his numerous relics. The Napoleon Museum was the last building constructed in Tuscany by Anatolij Demidov.

In 1859, Anatolij Demidov permanently left Florence to settle in Paris, disillusioned by the events that led to the downfall of the Grand Duchy and the annexation of Tuscany to the Kingdom of Italy. In 1863, to express his regret for having to leave Tuscany, he published in Paris La Toscane: Album monumental et pittoresque, an impressive collection, in large format, of drawings and lithographs by André Durand and Eugéne Ciceri, with text by A. De Saison (Paris, Lemercier, 1863). The monumental Album opened with a substantial series of views of the Island of Elba and the Napoleon Museum, followed by a series of splendid views of Tuscan cities and of Florence as it appeared shortly before the changes implemented by Giuseppe Poggi for Florence Capital of the Kingdom of Italy (1865-1871). Anatolij died in Paris in 1870 after a long illness. His nephew Pavel Pavlovič (1839-1885), son of Anatolij's older brother Pavel Demidov (1798-1840), became the heir and new owner of Villa San Donato.

The Album with photographs of Italian monuments

We cannot determine which one of the Demidov brothers decided to create the impressive photographic album with views of Italian cities and monuments presented here. The volume was preserved in the dispersed 'Bibliothèque de San Donato' and bears an elegant label that probably refers to its former location in the library of the Villa. The work is devoid of chronological indications, but some photos can be dated as far back as 1865, as they show a horse-drawn omnibus whizzing past Loggia dei Lanzi in Piazza della Signoria - in service since that very year - and the statue of Dante in the centre of Piazza S. Croce in Florence, which was sculpted by Enrico Pazzi in 1865, the year of the first celebration for the centenary of Dante Alighieri's birth. The Album entered the Uffizi Library as a 'gift by the Demidoff family' in June 1975, after the auction of the furnishings of Villa Demidoff in Pratolino, which was arranged by the heir of the family, Paolo Karageorgevič, in 1969.

Pavel Pavlovič and his fondness for revival

Anatolij Demidov's (1813-1870) nephew, Pavel Pavlovič (1839-1885), became the heir. He resided in Florence in the princely Villa San Donato from 1871 until the major auction of most of the art collections housed there, which he arranged in 1880 before relocating to his new residence in Pratolino. In 1871, Pavel married Elena Trubeckoj in his second marriage. The following year, the King of Italy confirmed the title of 'Second Prince and Princess of San Donato' to the Demidov couple, while Tsar Alexander II also recognised this title in Russia. This gesture aimed to maintain the connection between the Demidov family and Florence, which had already formed during Anatolij's time as the first prince of San Donato.

Like his uncle, Pavel Pavlovič was an avid collector who further expanded the number of artworks and objects displayed at San Donato, making the villa even more splendid, before deciding to sell off a large portion of the collections at the San Donato auction in 1880. With Pavel, Villa San Donato became a sort of 'stronghold' of the Demidov family, testifying to their immense wealth and importance. Perhaps for this reason, and also to live in a less oppressive climate compared to San Donato, in 1872 Pavel Pavlovič decided to acquire the park and what remained of the Medici villa in Pratolino, which had been inherited by the Grand Dukes of Lorraine. The ancient Medici villa was now in ruins, and the park and the surviving building of the Paggeria were in such a neglected condition that the restoration efforts in Pratolino lasted for several years. Initially, Pavel Pavlovič planned to build a new villa in 'Renaissance style' in Pratolino and contacted the French architect Anatole De Baudot, a student of Eugène Emmanuel Viollet Le Duc, to organise a competition for the best design. However, Pavel Pavlovič soon changed his mind, opting instead for a simpler expansion of the building of the Paggeria. Among the items from the Demidov collection preserved at the Uffizi, there are some renowned works by Viollet Le Duc, such as La cité de Carcassonne, with drawings made by his own hand, which was published in Paris in 1778. The great architect brought medieval art back in the spotlight and was famous for his 'in style' restorations of great French religious and civil architecture, such as the restoration of the Notre Dame Cathedral in Paris and precisely the reconstruction of the double walls of the town of Carcassonne, in the area of the Aude river, in the Occitan region, southern France.

While overseeing the restoration of Pratolino, Pavel Pavlovič also made various changes to the interior of Villa San Donato. One of the most peculiar was the relocation of the Demidov library along the nave of the ancient medieval church of San Donato. The church had been purchased during Anatolij Demidov's time because it was adjacent to the villa. In 1877, Pavel Pavlovič requested and obtained authorisation from the ecclesiastical authorities to 'desecrate' the building to carry out civil works.

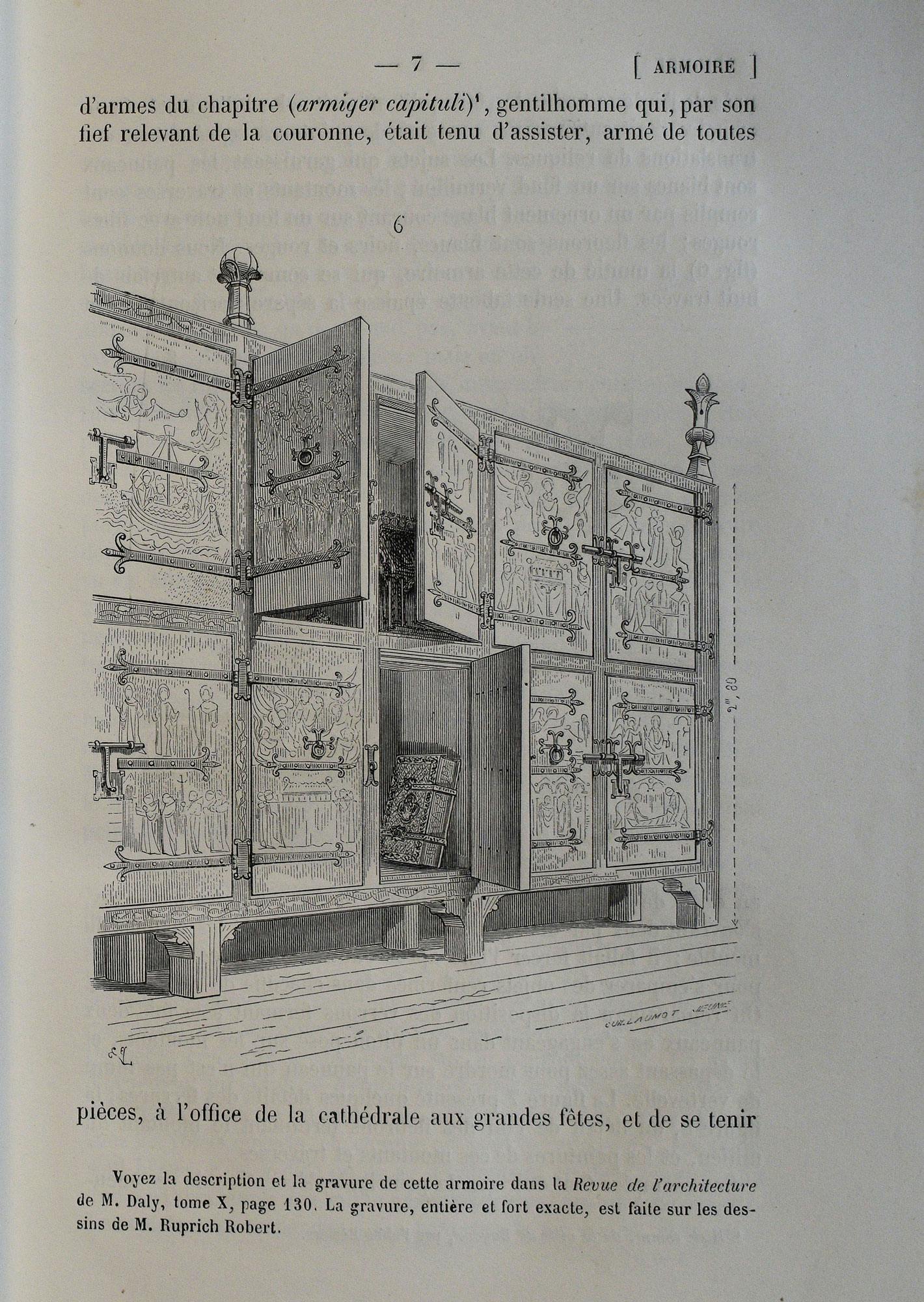

Pavel Pavlovič was a collector with an even more eclectic taste than his uncle. For San Donato, he acquired many medieval art objects, such as chests, precious fabrics and armours. As a matter of fact, it was in line with the fashion of the time to reconstruct entire environments 'in style' to evoke atmospheres of a reinvented, rather than real, Middle Ages. Therefore, he had the church, which housed the library, decorated with ancient frescoes that were restored and transferred to panels. The paintings described the popular legend according to which the church of San Donato was consecrated on February 2, 1187, the day a group of Crusader knights, led by Pazzino de' Pazzi, gathered there to receive the bishop's blessing before departing for the Holy Sepulchre. Furthermore, in Villa San Donato, he added two more rooms evoking the deeds of the Crusaders, both decorated 'in medieval style': the San Donato Hall, with coffered ceiling adorned with coats of arms of Crusader knights, and the Arms Hall, with ceiling decorated with war emblems. As a consequence, it is not surprising to find among the volumes from the dispersed library of San Donato a well-known text of the time, the Dictionnaire raisonné du mobilier français de l'époque carlovingienne à la Renaissance, a repertory published in Paris in 1872 where the French architect Viollet-Le-Duc meticulously described, with beautiful drawings made of his own hand, the objects of common use in the Middle Ages: from furniture to jewellery, clothing and weapons.

Author's note: In the text, we have preferred to use the Russian transcription 'Demidov' instead of the French form 'Demidoff', widely used in Tuscany throughout the 19th and 20th centuries. This choice is motivated by requirements of historical and linguistic correctness, and by the need for consistent dissemination to an international audience.