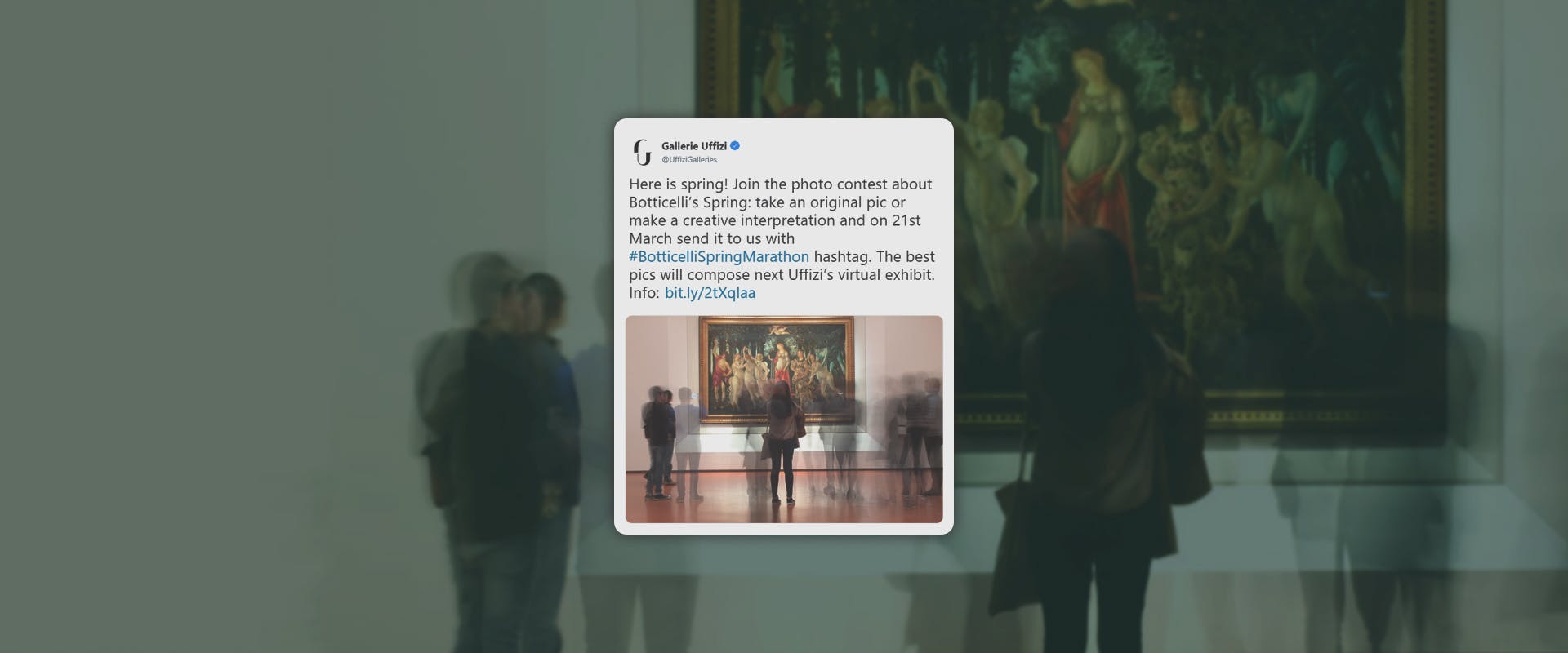

#BotticelliSpringMarathon

On 21 March 2018 the Department of Digital Communication of the Uffizi Galleries launched an international campaign on Twitter entitled #BotticelliSpringMarathon in which they invited their followers and the most important museums in the world that preserve works by Botticelli to share a spring greeting on the Uffizi profile in recognition of the great Florentine master’s art. The initiative was associated with a photographic competition, a one-week digital marathon where Uffizi visitors and online users from all over the world were asked to send their “own” visions of one of the most iconic works of the museum’s collection, the subject of genuine veneration, to @UffiziGalleries: Botticelli's Spring. In a few hours the campaign went viral, social and print media were abuzz, it spread around the world, boasting the participation of important museums that decided to pay homage to the Uffizi’s initiative by posting details associated with Spring from the masterpieces by Botticelli they preserve: the Louvre, the Prado, the National Gallery in London, the Puškin Museum, the Hermitage, the National Gallery in Edinburgh, the Isabella Stewart-Gardner Museum, the Museum of Houston, the Museum of Strasbourg and the Italian Poldi Pezzoli and Giorgio Cini Foundation were museums that responded with enthusiasm and sympathy to the Uffizi “digital Spring festival”.

1. Running the world

All the tweets from the Italian and international museums and galleries that took part in the social campaign are visible in the first section of this Hypervision entitled “Running the world”, while the more interesting users’ photos selected from the contest are grouped according to theme in the following seven sections. To be immediately redirected to this section’s contents please click on the paragraph’s title.

2. Spring at home

The first chapter is dedicated to photos taken by visitors directly in front of the work, in the gallery. From the point of view of semiotics and communications theory, as will be shown in more detail, these shots are united by their “spectrum”, in accordance with the definition Roland Barthes provides in Camera Lucida. They are images in which the focus, with all the sign and meaning implications that ensue, is on the act of immortalizing the subject of the photograph and then analysing the emotional effects on the spectator, that is the last “user” of the photograph, the observer in a subsequent step.

3. Digital Botticelli

The third section entitled “Digital Botticelli” is still connected to the theme of photography but is more focused on the intentions and motives of the Barthesian “operator” this time, that is, the person who takes the picture, its author. It provides the opportunity for a broader consideration, that Walter Benjamin identified as inherent to the transformation of the work of art into an object of consumption, typical of the technological age. The use of the photograph of a masterpiece as a metalanguage or, as Roland Barthes put it, “intertext” (“I take a photo of the person taking a photo of Botticelli's Spring or of myself with a selfie”) made possible by the widespread and now standardized use of digital devices, often mobile phones and other devices rather than cameras, which have become widely used as virtual message boards ready for sharing on social networks or as albums of instantaneous memories that can be edited in real time.

4. Botticelli Reloaded

From digital technology to digital art, the fourth section leaves the field open to users and their free, ironical and post-modern reinterpretations of Botticelli’s masterpiece, using software for the processing of digital images.

5. Botticelli Attack

And still on the theme of free creativity, taking inspiration from art as a sort of “game”, the fifth section is a collection of photos by people who, in imitation or in fun, have paid homage to The Spring, confirming, if that is still necessary, how much Botticelli has really penetrated – and is still strongly present in – popular contemporary culture, to the point of inducing many critics to speak of a veritable “fetish” of our times, in an anthropological sense. The history of the creation of the contemporary Botticelli myth is intriguing. It began in England in the middle of the nineteenth century, at the end of the Georgian age, and was fuelled, some ten years later in Victorian times by the Confraternity of Pre-Raphaelites, marking the turning point and arriving in the United States between the nineteenth and twentieth centuries with a domino effect involving the whole of Europe. Here perhaps the first “pop” turning point took place for the Florentine genius in the 1940s, and spread into contemporary culture through typical twentieth-century media: photography, fashion (understood as a mass phenomenon) and above all video.

6. Springspired

Quoting, dismantling, fragmenting, dismembering and reconstructing, even cannibalizing the surroundings – as well as the idea – are all hallmarks of contemporary culture, as had already been perfectly intuited by the pioneer of reflection on the “post-modern condition”, Jean-François Lyotard and, in Italy, Umberto Eco, who among others defined this phenomenon perfectly. Not even Botticelli's Spring seems to escape these dynamics or the desire of followers to build semantic networks of hypertext around it in accordance with their own codes of communication, which by no coincidence are those of the internet. The sixth chapter of the Hypervision investigates this link, based on the suggestions of the philosopher and the semiologist: “Springspired”.

7. Krash

The seventh section looks at the selection of The Spring as a true mass media icon of our time, an image so deeply rooted in the contemporary world view to become not only an anthropological fetish but an object of daily consumption, proof of the confirmation in twenty-first century pop culture of the process of transformation of art into consumer goods: the transformation of Botticelli into a “brand”.

8. One Botticelli does not mean it’s Spring

The name Botticelli has become so “branded” worldwide that quite a few followers have even rendered the two absolute icons of the Florentine master interchangeable in a free and unstoppable association of ideas (or stream of consciousness?) by superimposing the idea of The Spring onto the idea of the Birth of Venus. Perhaps this is because both imply the generation of new, positive forces related to nature, because both have the same strong “nature” element just as both have the same aesthetic and erotic principle embodied by Venus; those principles that in any case reside in an idealized vision of femininity... or perhaps because the name Botticelli alone has become an “umbrella brand” that brings together and represents the individual “brands”. In any case, no error is ever random, no slip is devoid of meaning and we would like to dedicate the last section of this Hypervision - that, with equal irony, we have called “One Botticelli does not mean it’s Spring” - to these more or less conscious and ironic “errors” made by followers who “thought of” The Spring but “said” Venus.

Credits

Project and texts by Simone Rovida from the Department of Digital Strategies of the Uffizi Galleries.

Published 20 March 2018

Graphics by Claudio di Giuseppe