On Being Present - vol. I

Recovering Blackness in the Uffizi Galleries

- 1/19Intro

There is no healing presence when the wounded past is erased from our cultural memory and archive. The void this erasure produces fills empty gestures with violence rather than possibilities of relation.

Nana Adusei-Poku

On Being Present Where You Wish To Disappear; E-Flux Journal # 80; (March 2017)

For anyone who has walked the floors of the Uffizi or of Palatine Gallery in Pitti Palace with an acute eye for detail, it may have been possible to miss the presence of Black African figures in the collection. This is not due to their lack of representation, counting over 20 figures in the main spaces alone, but speaks more to the historical and art historical frameworks within which viewers navigate these spaces contributing to their obscurity. On Being Present is a research project with a virtual platform via the website of the Uffizi Galleries launched in February 2020 as a collaboration between Black History Month Florence and the Uffizi Galleries that highlights the histories and historical context of the African figures present in a range of paintings throughout the Gallery of Statues and Paintings and Palatine Gallery. Drawing upon a plethora of scholarly works and exhibitions in recent history, this project is a recovery of Blackness from directly within one of the most iconic collections of art in the world.

In her 2017 article in E-Flux Journal # 80 “On Being Present Where You Wish To Disappear”, Nana Adusei-Poku writes about the “Black Abyss” and the ways in which the writing on history has the capacity to swallow fundamental fragments that attest to presence and persistence across a temporal spectrum, essentially vanishing evidence of existence. The range of figures examined in this project, the majority of which are on display in the collections of the Gallery of Statues and Paintings and Palatine Gallery, have peered out from their frames for centuries as witnesses to presence in the psycho-social sphere of Italian and European history. The significance of these figures extends beyond their meaning and interpretation in these masterpieces of Art History. These figures confirm the presence of the continent of Africa in the consciousness of the commissioners of these works from a range of artists across time and speak to the incredible cultural exchange that was taking place when these works were being made, indeed, across all of written history. This presence is simultaneously a physical reality and a metaphysical one both of which guided the shaping of “Western” history with its inclusions and omissions.

The fact that the historic presence of Black Africans in the territory now known as Italy is mainly common knowledge amongst scholars of these periods of Art History does little to rectify the distance between scholarly circles and the viewing public of one of the most frequented museums of the world. The Uffizi Galleries Hypervisions provides a unique opportunity to render accessible views and reflections on their collections that extend beyond the guidebooks that have overlooked most of the figures that are addressed herein. It is our hope that this project may contribute to a more profound meditation on the cultural history that the museums hold, and may spark future public conversations and scholarly research in the years to come. We hope simultaneously to assist tour guides and visitors to the museums wishing to address these histories but lacking the sources to do so. Being present may seem to be the least anyone can do, but to be consciously present requires a willingness to bear witness to what has been overlooked and to force it to the surface of our understandings and our misunderstandings.

Justin Randolph Thompson | Director and Co-Founder of Black History Month Florence

- 2/19Vittore Carpaccio

Gli alabardieri

1490-1493

Oil on wood, 68 x 42 cm

Uffizi Galleries, Gallery of Statues and Paintings, Room 21

Inv. 1890 n. 901

Carpaccio has a pronounced interest in depictions of black Africans who appear in all his narrative cycles, and in various other paintings. These include black gondoliers and boatmen, known to have existed in Renaissance Venice, often flamboyantly dressed, with eye-catching and expensive hats. The cut-down fragment of a painting on wood known as Gli alabardieri is one of the more enigmatic of Carpaccio’s oeuvre as the subject of the painting is not known. It is thought to have been part of a religious historical narrative, but the main narrative cycles by Carpaccio are all on canvas, so maybe it was a freestanding painting. Possible subjects are Raising the Cross, Finding the True Cross (both suggested by the beam lying across the bottom of the painting, with a small hole in front) or The Martyrdom of the 10,000 Christians on Mount Ararat. In all these cases, it is likely that the extant fragment would have been a scene on the side, where a sub-plot was being enacted that added texture and context to the main story. Many Renaissance representations of sub-Saharan Africans appear in small groups like this, often in imagined non-European locations, where historical episodes are re-imagined in the fifteenth or sixteenth centuries. Carpaccio belongs to a group of Venetian painters who believed that the authenticity of an episode could be buttressed by the inclusion of as much verifiable detail as possible, especially in relation to costume, landscape and architecture. For paintings set in Venice, this was easy to do, but for foreign scenes, there were difficulties. Given the topics of the narrative cycles, set in the Holy Land or North Africa, Carpaccio’s paintings are legitimately peopled by Jews, Ottomans, Mamluks, North and sub-Saharan Africans. Carpaccio had never been to these places, but copied relevant details from woodcuts in a 1486 travel book to Egypt and the Holy Land, and from The Reception of the Ambassadors in Damascus by an unknown painter, dated 1488-99, that included supposedly authentic details.

- 3/19Vittore Carpaccio

The central section of this fragment contains two expensively dressed outsiders – a Jew and a very high-ranking Mamluk official wearing ‘horned’ headgear – surrounded by a variety of soldiers holding pikes and standards, one proclaiming Roman allegiance by sporting the letters SPQR. Elaborate headgear is something of a Carpaccian speciality, and the sub-Saharan African next to them has a tufted cylindrical red hat which approximates to a zamt worn by Mamluk soldiers. Red was an expensive colour and denoted prestige. The first two men are presented in half-profile, their faces full of individual detail, and have beards indicating authority. The clean-shaven black African faces the viewer more squarely, making his physiognomy less clearly visible, and one impression is of the whites of his eyes and three white teeth set against the backdrop of his black face. There is another black African to his right. A turbaned man with darker skin on the right-hand edge seen in older reproductions was a later addition who has now been removed. The central black African is not represented as a servant, or a routine bystander, but as a soldier, an occupation known to have included people of sub-Saharan African descent, both in Renaissance Italy and under the late fifteenth-century and early sixteenth-century Mamluk sultanate. In the 1490s a recently formed unit of 500 black slaves was expressly given permission by the sultan to wear the red zamt, previously reserved to the Mamluk military elite. Whether Carpaccio could have heard news of this, or coincidentally thought of inserting a black soldier wearing a zamt into his composition, is unclear.

Text | Kate Lowe

- 4/19Albrecht Dürer

Adoration of the Magi

1504

Oil on wood, 99 x 113.5 cm

Uffizi Galleries, Gallery of Statues and Paintings, Room 45

Inv. 1890 n. 1434

The Uffizi owns three especially famous paintings of the Magi, by Gentile da Fabriano (1423), Andrea Mantegna (early 1460s), and Albrecht Dürer (1504). The story of the Magi is told in the Gospel of St. Matthew, a brief account of sages/astrologers who travel from the East to worship and bring precious gifts to the infant Christ. During the Middle Ages many details were added: there were three Magi; they were sovereigns as well as sages; one was young, one middle-aged, and one old; and rather than just traveling together from the “East,” they were increasingly said to come from three different lands, over which each ruled. Gentile’s picture is typical of Italian works from the early 1400s, in showing splendidly dressed kings and a vast entourage, many of whom wear Middle-Eastern garments, accompanied by African and Asian animals. But no black African figure appears, either among the Three Kings or their followers. By this time, German artists and writers had begun to include a black African among the Magi, perhaps to denote European hopes that the Christian Emperor of Ethiopia would prove an ally in conflicts with Islamic powers. The first major Italian to include such imagery was Andrea Mantegna, whose composition was created in Mantua, in northern Italy. Mantegna included both a black Magus as well as three other black men among the attendants of the Magi; their turbans link them to the Islamic world.

- 5/19Albrecht Dürer

Albrecht Dürer’s approach is broadly similar to Mantegna’s. They both characterize their African Magus as the youngest of the three, and position him furthest from the Christ Child. However, in Dürer’s Adoration, the two African figures in the foreground – Magus and servant – are contrasted. The Magus has darker brown skin, and his facial features and short, tightly curled hair are those conventionally assigned in this period to Africans. But his elegant garments and dashing hat are those worn by fashionable young European men, like Dürer himself. Of all that he wears, only his gold earring marks him as African. (A few years later, a Venetian writer criticized such earrings as “Moorish.”) The servant has a comparable physiognomy, but his complexion is much lighter, and he wears a turban. An unexpected hierarchy is established here: European dress but also darker skin are associated with the ruler, while his underling is distinguished by paler skin and a Muslim headdress. In other Renaissance images of the Adoration of the Magi, it is far more common for the ruler to be relatively light-skinned, and subordinates darker.

Artwork detailsAdoration of the MagiPainting | The Uffizi - 6/19Albrecht Dürer

Dürer was clearly fascinated by Africans. An African figure appears in his own coat of arms, in woodcut form, and two elaborate, finished drawings of African models by him survive. One of these is in the Uffizi as well: it represents a handsome if slightly melancholy young woman named Katherina, the probably enslaved servant of a Portuguese official in Antwerp. Dürer’s Magus is wonderfully imagined, but the portrait drawing takes us closer to the reality of the African presence in Renaissance Europe.

Text | Paul Kaplan

- 7/19Piero di Cosimo

Perseus frees Andromeda

1510-1513 c.

Tempera grassa on panel, 70 x 120 cm

Uffizi Galleries, Gallery of Statues and Paintings, Room 28

Inv. 1890 n. 1536

Magic and Modernity: Apprehending the African Presence in Piero di Cosimo’s Liberation of Andromeda

In his second edition of the Lives of the Artists (1568), Giorgio Vasari claimed that “Piero never made a more lovely or more highly finished picture” than the Liberation of Andromeda, singling out the Leonardo-inspired marine monster for special praise. Vasari proceeded to call attention to the right “foreground [where there] are many people in various strange costumes, playing instruments and signing; among whom are some heads, smiling and rejoicing at seeing the deliverance of Andromeda, that are divine". Meanwhile, the celebrated Latin poet Ovid’s original description of the celebrations that followed Perseus’s rescue of the princess – “Lute, flute and song resound on every side / Glad proof of happiness” (Metamorphoses, IV) – is captured specifically by Piero’s pair of musicians on the shore.

Few artists in Renaissance Italy embodied – and reconciled – the Apollonian call to order and form and the Dionysian passions to the extent that the two contradictory aspects coexisted in Piero di Cosimo and his art. And so it seems all the more appropriate to find these seeming opposites reflected, even if obliquely, in the same composite instrument played by the black African musician at right, an unprecedented figure in Florentine art. While the lyre-like lower part of his string-wind instrument can be read as a reference to the Sun God, the bladderpipe (originating from the ancient phusalis) joined to its upper section makes for a tempting reference to the satyr Marsyas, the doomed follower of Dionysus alternatively portrayed with a bagpipe-like instrument or his more traditional panpipes. Associations with higher reason and logic on the one hand and with baser instincts on the other thus have been united in a single instrument. What remains of greatest human interest to us here, however, is the origin and significance of the musician playing this exotic invention.

Artwork detailsPerseus frees AndromedaPainting | The Uffizi - 8/19Piero di Cosimo

Black musicians appear very infrequently in Renaissance painting. Virtually nonexistent, it should be mentioned, are representations of black Andromeda, despite the maiden’s well-known Ethiopian origins. While he remains something of a peripheral figure, Piero’s black musician is nonetheless a prominent presence and, more broadly, bears witness to the painter’s fascination with foreign lands and peoples. As was also the case with the contemporary court painter Andrea Mantegna (c.1430/31–1506), who depicted what appears to be a black African drummer-fifer in his antique-inspired Introduction of the Cult of Cybele in Rome of 1505–6 (National Gallery, London), race and ethnicity emerge as another important part of Piero’s richly diverse visual grammar. While Mantegna’s interests tend toward the archeological, Piero’s may best be described as more anthropological in spirit. If there is anything that ongoing scholarly investigation of Renaissance social and cultural practices has shown us, it is that the field of art history benefits immeasurably when interpretation moves outward into the lived world, rather than solely inward toward erudite literary sources. In the case of Piero’s Liberation, the conspicuous African and Mamluk presence (the latter visible in the white turbaned figure of King Cepheus) complicates the narrative’s meaning in new ways, identifying it as something more profound and less straightforward than an entertaining tall tale.

text | Dennis Geronimus

Artwork detailsPerseus frees AndromedaPainting | The Uffizi - 9/19Portrait of Alessandro de’ Medici by Vasari in conversation with his Portrait by Bronzino

Giorgio Vasari

Portrait of Alessandro de’ Medici

1534-1535 c.

Oil on wood, 157 x 114 cm

Uffizi Galleries, Gallery of Statues and Paintings, Room 83

Inv. 1890 n. 1563

Agnolo di Cosimo Tori detto il Bronzino

Portrait of Alessandro de’ Medici

1534-35 c.

Oil on tin, 16 x 12.5 cm

Uffizi Galleries, Gallery of Statues and Paintings, Deposits

Inv. 1890 n. 857

Here we contrast two portraits of duke Alessandro de’ Medici (1510-1537) of Florence by two of the most noted artists of the Italian Renaissance, Giorgio Vasari (1511-1574) and Agnolo Bronzino (1503-1572). Both worked in Florence but only Bronzino was born there. Both knew duke Alessandro personally, which is important to know when considering how accurately the two portraits represent the young duke. Alessandro, illegitimate son of Lorenzo de’ Medici erstwhile duke of Urbino and a black African slave woman named Simonetta, was made duke in 1531, by the emperor Charles V, to ensure that Florence would remain a satellite in the contest against France to dominate Italy. So, Alessandro was “black” in the old Louisiana sense of the term; that is, one drop of African blood is enough to qualify a person as black.

But here the question is not his race, which I have addressed elsewhere, but what are these portraits telling the viewer about Alessandro and his role in government. Vasari has painted the duke in armor (not the only such portrait of him), while Bronzino presents us with a more relaxed picture of Alessandro, although he is wearing a chainmail vest under his tunic.

Vasari’s portrait is crystal clear in its intention. This is a dynastic painting. Executed in 1534, Alessandro is depicted wearing a full suit of silver armor, seated in a cave looking out of the opening over a panorama of Florence in the distance. The young duke is clearly presented in his role as sovereign and protector of the city. His role of ruler is signified by the wooden baton (or fascio), from the Roman era, signifying his right to rule and his responsibility to rule well.

- 10/19Portrait of Alessandro de’ Medici by Vasari in conversation with his Portrait by Bronzino

Bronzino’s portrait was painted in 1534-1535, after the death of the duke’s uncle and patron, Pope Clement VII. His tunic is black, in mourning for Clement. He felt very exposed to his enemies then, so the vest shows that he has not let down his guard. Yet, the portrait conveys a sense of informality, of intimacy, as no Medici or other royal iconography is pictured. Clearly, this was not a dynastic painting meant to convey his rulership status to viewers. His facial expression is almost soft, vulnerable, not the expression designed to convey power. It may have been intended as a gift for Alessandro’s mistress, Taddea Malaspina, whose family lived in the palazzo Pazzi, next to the Medici palace in Via Larga. They produced two children, a boy, Giulio, and a girl, Giulia, named in honor of his uncle and patron (Giuliano). It was said that Alessandro spent so much time there that he practically could be said to have lived in that palace.

So, we see both sides of the young duke, the public and the private, the ruler and the vulnerable young man. The first intended for public consumption and instruction has a didactic purpose: Alessandro as the sovereign and protector of Florence. The second seems like a gift intended for private and intimate consumption, perhaps for a loved one.

text | John K. Brackett

- 11/19Cristofano dell’Altissimo

Portrait of aṣe Lǝbnä Dǝngǝl

1552-1568 c.

Oil on wood, 58 x 43 cm

Uffizi Galleries, Gallery of Statues and Paintings, Corridors

Inv. 1890 n. 1

The inscription on this portrait identifies its subject as “Atanadi Dinghil, great king of the Abyssinians, commonly called Prester John.” Abyssinia, derived from Arabic, was a longstanding name for the Christian empire of Ethiopia in the Horn of Africa, a kingdom that existed in various forms from the twelfth century until a coup deposed Emperor Haile Selassie in 1974. (Under the Axumite Empire, the region had converted to Christianity in the fourth century.)

The man represented in the painting was indeed an Ethiopian king (or negus, the traditional title of the Ethiopian monarch), a member of the dynasty that had ruled Ethiopia since 1270 and believed itself descended from the biblical king Solomon. Born in 1496 or 1497 with the given name of Lǝbnä Dǝngǝl, he succeeded to the throne in 1508 and reigned until his death in 1540. Though he was sometimes called by his throne name of Dawit, or David, Europeans referred to the Ethiopian negus as ‘Prester John,’ the name of a legendary ruler of a Christian realm in the East with incredible wealth and great military power, whose mythos had endured over centuries. Europeans hoped for an Eastern ally in the struggle against Islam, and the constructed personage of Prester John figured into international political strategies and geographical discovery, his image developing alongside historical, theological, and mythological conceptions of Asia and Africa.

In 1533, an embassy sent by aṣe Lǝbnä Dǝngǝl from Ethiopia in 1526 arrived in Italy carrying letters and gifts to the pope – gifts that included a portrait of the negus himself, although the date of 1532 on the panel indicates that it was likely painted in Portugal from an image or description provided by members of the embassy who had spent time in his presence. Regardless, his likeness traveled great distances, carrying information from Africa to Italy; upon presentation to the pope, the object staged an encounter between two individuals who could never meet in person.

The Uffizi’s painting is a copy, or perhaps a copy of a copy, of the portrait originally presented to Pope Clement VII. In 1552, Duke Cosimo I de’ Medici sent the court artist Cristofano dell’Altissimo to Como with instructions to replicate, in a standardized format, the celebrated portrait collection of Paolo Giovio, a humanist scholar and historian who had personally witnessed the Ethiopian ambassador’s ceremonial presentation to Pope Clement VII, and afterwards translated aṣe Lǝbnä Dǝngǝl’s letters into Latin. In the second edition of Giorgio Vasari’s Vite, published in 1568, we learn that Cristofano copied over 250 of the uomini famosi in Giovio’s vast museo. According to Vasari, the painted panels, each framed in walnut, were meant to hang in Cosimo’s guardaroba nuova in the Palazzo Vecchio. During the reign of Cosimo’s son Ferdinando I, however, the series was installed as you see it today, just below the ceiling in the Uffizi’s corridor.

testo | Ingrid Greenfield

- 12/19Cristofano dell’Altissimo

Portrait of Alchitrof

1552-1568 c.

Oil on wood, 60 x 45 cm

Uffizi Galleries, Gallery of Statues and Paintings, Corridors

Inv. 1890 n. 3065

This handsome picture was part of a series of “famous men” painted for Duke Cosimo I de’ Medici in the mid-sixteenth century.

Its subject is Alchitrof, “king of Ethiopia,” who is richly dressed and holds what seems be an empty wooden frame. Alchitrof’s eye-catching costume confirmed his exoticism to European viewers. In the visual arts of the sixteenth century, clothing even more than physical features was used to classify and make sense of the peoples of the world, as evidenced in the popular genre of the costume book.

Yet these classifications were often problematic and confused. No Ethiopian king by the name of Alchitrof is actually known, and no Ethiopian of the period dressed in the manner shown here. Alchitrof’s feathered headdress and the chained pearls hanging from his lower lip more resemble sixteenth-century European images of South American dress than anything known in Africa. None of this is really surprising: ignorance, a generalized fascination with the unknown, and a growing sense of racial hierarchies meant that Europeans frequently confused the peoples of Africa and the Americas, replacing observation with stereotype and fantasy.

Ironically, Cosimo I’s collection of portraits was based on a series of pictures of “famous men” that was known for its precision. Its patron, Paolo Giovio, insisted on the accuracy of his portraits, and went to great lengths to assure that the pictures hanging on his walls were reliable representations of their subjects. His collection, housed in the northern Italian city of Como, was widely copied—in the case of this image of Alchitrof by the painter Cristofano dell’Altissimo—and was thus an important tool in diffusing ideas about what these “famous men” (in fact almost all male, and all European) looked like.

One curious detail in this portrait of Alchitrof is the empty frame in the foreground. In another copy of the picture, today in Vienna, the object seems to be a mirror that rather awkwardly reflects the king’s garment. Smooth glass mirrors were a relatively new invention, perfected in Venice, circulated through trade, and admired for the pristine reflections they provided. Alchitrof’s assumed interest in the mirror would put him in good company with elite consumers throughout Europe; it would also align his portrait with other Renaissance portraits in which the sitter holds a prized object in order to signify wealth and good taste.

But in the case of an African king in a portrait made for Europeans, the mirror likely held other meanings. It might have signaled the presumed fascination of an outsider with Italian manufacture, subtly communicating a hierarchy of culture between those with technological know-how and those who could only admire it. Or it might have hinted at the idealized role of the portrait as a mirror that duplicates the world as it is seen. This would have been a clever way of assuring European viewers that this image was an accurate representation of Alchitroff as he actually existed in the world.

text | Elizabeth Rodini

- 13/19Justus Suttermans

Madonna Domenica delle Cascine, la Cecca di Pratolino e Piero moro

1634 c.

oil on canvas, 100 x 94 cm

Uffizi Galleries, Gallery of Statues and Paintings, Room 93

Inv. P. Imp. 1860 n. 1356

From its rediscovery in 1977, this painting has been recognized as an unusual work by Suttermans, who almost exclusively painted official portraits of members of the Medici court. The work is one of two similar paintings documented in different Medici residences: their different dimensions and frames confirm that they were not the same work. The replication of the painting leaves no doubt that Suttermans’ composition was greatly admired, since different members of the family desired different versions of it.

The painting has been connected frequently to a burlesque tradition of Florentine painting and to the genre subjects popular in both the North and South Netherlands, given the artist’s Flemish origins. The popularity of carnival subjects among northern artists suggest the likelihood that the work belongs to a carnivalesque context. The theatricality of the composition, heightened by its Caravaggesque lighting, appears to confirm this. A key element to understanding the meaning of the work is the hand gesture made by Piero behind Cecca’s shoulder, which would have been recognizably vulgar for the standards of the time. Indeed, the work appears to contain all of the characteristic aspects of the carnivalesque identified by Bakhtin: the bringing together of unlikely groups of people, the inversion of status, and the subversion of societal norms.

Contemporary documents provide significant information about the old countrywomen depicted by Suttermans: both Domenica — sometimes called by a shortened version of her name, “Menica” — and Cecca are recorded regularly in Medici account books in which the expenses for food stuffs brought by them to the court were registered. “Monna Domenica delle Cascine,” however, was also paid for other services. She was rewarded more than once for some form of comic performance (“fare il Buffone”).

Artwork detailsMadonna "Domenica delle Cascine", la Cecca di Pratolino e Pietro moroPainting | The Uffizi - 14/19Justus Suttermans

It is striking that we know so much about the two countrywomen — that one sold geese to the court and the other brought quinces — but that we know so little about “Piero moro.” In a letter of 1634, Cardinal Giovan Carlo de’ Medici, wrote to his younger brother Mattias, from the Medici Villa at Pratolino, stating that after having hunted partridges and hares, they were entertained while resting by watching the court painters Suttermans and Giovanni di San Giovanni paint: “Justus made portraits of those countrywomen” (“Giusto faceva ritratti di quelle contandine”). Piero is not even named here, although the letter must refer to the execution of this work. His name survives in only one inventory and he is otherwise remembered generically as a “moor.” No one doubts, however, his existence or that he must have been a member of the household of one of the Medici family, either of Cardinal Giovan Carlo or of his older brother, the Grand Duke Ferdinando II.

Pratolino, where the composition was born, may provide a clue to the artist’s intent in grouping these three figures together. Over fifty years before the work was painted, during the construction of the Medici villa and its elaborate gardens, Francesco I had resorted to the use of forced labor in the construction of an artificial lake. These countrymen had suffered miserable working conditions, many of whom became ill during the harsh winter of 1578-9. The Grand Duke was strongly censored for these abhorrent practices by several contemporary chroniclers. Shortly after work on the lake and palace at Pratolino were complete, the park was broken into and vandalized: the aviary was destroyed and the birds contained within it were released, the pipes that furnished water to several fountains were damaged, and — most remarkably — the noses were cut off of numerous statues. A sign was left at the site, leaving no doubt that it was some of the previously abused laborers who performed these acts.

Pratolino nonetheless contained numerous representations of farm workers in its now lost sculpture and automata. These idealized figures would have contrasted strongly with the actual working conditions of farmers employed at the estate. Already from the time of Ferdinando I, later Grand Dukes sought to distance themselves from Francesco I’s labor practices. If a memory of the origins of Pratolino in the abuse of a peasant workforce was still vivid two generations later, the painting may have been partly intended to demonstrate the Medici’s benevolence towards their farmworkers. At the same time, the inclusion of Piero as a foil to the two old women insures that something else is happening in the painting. The hand gesture, which refers to sexual intercourse, introduces a lewd element, and opens the door to kinds of speculation that belong to the ribald sense of humor that was typical of the men of the Medici court.

Piero is characterized by his youth, black skin, and exotic and costly pearl earring. He is thus a part of the court and its world of privilege. The country women are old, wizened, and poorly dressed — the elbow of Cecca’s sleeve is clearly worn and mended. The two women look only at each other. Thus, Piero’s gesture is unseen by them and is meant for us, as external viewers and presumably members of the courtly elite. Piero thus seems to have the upper hand, linked to the world of power and authority rather than to that of the poor countryfolk. Yet, the women were surely free while he was almost certainly an enslaved individual, far from his family and place of origin, and entirely dependent for his subsistence on his aristocratic owners.

text | Bruce Edelstein

Artwork detailsMadonna "Domenica delle Cascine", la Cecca di Pratolino e Pietro moroPainting | The Uffizi - 15/19Anton Domenico Gabbiani

Portrait of four servants of the Medici court

1684

Oil on canvas, 205 x 140 cm

Uffizi Galleries, Pitti Palace, Palatine Gallery, Deposits

Inv. 1890 n. 3827

Anton Domenico Gabbiani’s first biographer and erstwhile student Ignatius Hugford described two Gabbiani paintings that hung in the Medici Villa di Castello, just outside Florence: “various portraits of several youths of barbarous nations who lived at the court of Grand Duke Cosimo III, that is Moors, Tartars, Cossacks, etc., various low level Courtiers; among them is a dwarf who holds a plate in his hand with a few leaves of fresh spinach, in order to indicate his particular inclination for passing on the business of other people, in which skill, he [the dwarf] stands out above all others” [1]. This description is rich. In the details it conveys, we can identify the Portrait of four servants of the Medici court displayed here, and more importantly, grasp the documentary quality of the painting’s imagery. It was common practice in the 16th and 17th centuries for European courts to collect bizarre or unusual human beings—what Bernadette Andrea has called “living, breathing luxury items”—including dwarves and foreign slaves [2]. These individuals served a primarily decorative purpose, embodying (quite literally) the geospatial purchasing power of the sovereign and entertaining the denizens of the court with their appearance, with humorous antics, and comedic performances. In Florence, there were many black court “buffoons,” as they are frequently called in surviving sources. Simultaneously peripheral and central to court life, such entertainers were well placed to observe a large variety of activity and behavior—just as the prominently placed plate of spinach in Gabbiani’s painting suggests.

Gabbiani depicts the entertaining context of the four servants through their interactions within the frame of the painting. The three central (and more dramatically “different”) figures gather in a relatively orderly, well-choreographed fashion, while the two dwarves and their monkey engage over the spinach. On the right, the stone column and red silk curtain frame the image, referencing standard conventions of formal portraiture, while on the left, a rather dissolute and unkept older white man—identified by Marco Chiarini as “Corporal Buccia" [3] crowds his way into the frame like a seventeenth-century photobomb. The pained, almost apprehensive expression on the young black man’s face suggests that the late arrival is unwanted and even unexpected; the impression of discomfort is magnified by Buccia’s pointing hand, which rests suggestively on the black man’s hip. Presumably, this gesture and Buccia’s looming appearance referenced some gossipy event or a lazzi (slapstick routine or joke) that would have been familiar to contemporary viewers.

- 16/19Anton Domenico Gabbiani

Indeed, early Florentine viewers of this painting would have recognized the sitters as familiar and recognizable people. The precise identification of the black man shown here is rendered difficult by the fact that most black men in Florence are described in contemporary sources with the nickname “il Moro” (lit. “the Black”). A plausible candidate, based on the relative youth of Gabbiani’s sitter, is Mehmet, “Turco & etiope” (lit. “Turkish & Ethiopian,” though more accurately, “Muslim & African”), who was baptized with the name Giuseppe Maria Medici in 1685. [4] Mehmet described himself as being from Mussa, Borno, in modern-day Nigeria; he would have been around 14 when Gabbiani’s painting was made.

Gabbiani’s black African wears a luxurious silk cassock, belted, in the Ottoman style, with a soft cloth tied around the waist and Moroccan style slippers. A double strand of coral beads is visible at his neck. Such outfits were standard for enslaved African court retainers at the Medici court, reflecting what Monica Miller has called “black specularity,” both through the evident costliness of the outfit and its explicit racialization of the black wearer. [5] Documents from 1666, for example, detail an outfit made for the Morino or “black boy” belonging to Ferdinando II, presumably Ali Moro, who would have been about 10 at the time: [6] he received an “outfit in the Moorish style (alla moresca) made of green cloth, silk slippers, and stockings made in one piece and a long cassock down to the knee, all decorated with green trim”. [7] The accounts included 3 dozen buttons to decorate the front of the cassock. The outfit Gabbiani depicts here can be productively compared with that worn by the much younger black boy depicted in his Portrait of Three Musicians of the Medici Court (Florence, Galleria dell’Accademia, Museo degli Strumenti Musicali, inv. 1890, no. 2802).

The enslaved black singer, Giovanni Buonaccorsi, active at the Medici court from 1651 to his death in 1674, left one surviving poem, in which he described a group of court buffoons very similar to the one depicted here: “They are of the Court,” he wrote, “the Turks and dwarves, the bad Christians”. [8] Like Gabbiani, Buonaccorsi (and Mehmet, Ali, and even the biographer/painter Hugford) reminds us of the central presence of black Africans (and dwarves, Tartars, Cossacks) within the Medici court itself.

text | Emily Wilbourne

- 17/19Benedetto Silva

Domenico Tempesti

Portrait of Benedetto d’Angola Silva

Pastel on paper, 64 x 50 cm

XVIII secolo

Uffizi Galleries, Gallery of Statues and Paintings, Deposits

Inv. 1890 n. 2522

Antonio Franchi (?)

Portrait of Benedetto d’Angola Silva

Oil on wood, 73 x 87.5 cm

1709-1710

Florence, Medici Villa La Petraia

Inv. Oggetti d’arte Petraia n. 13

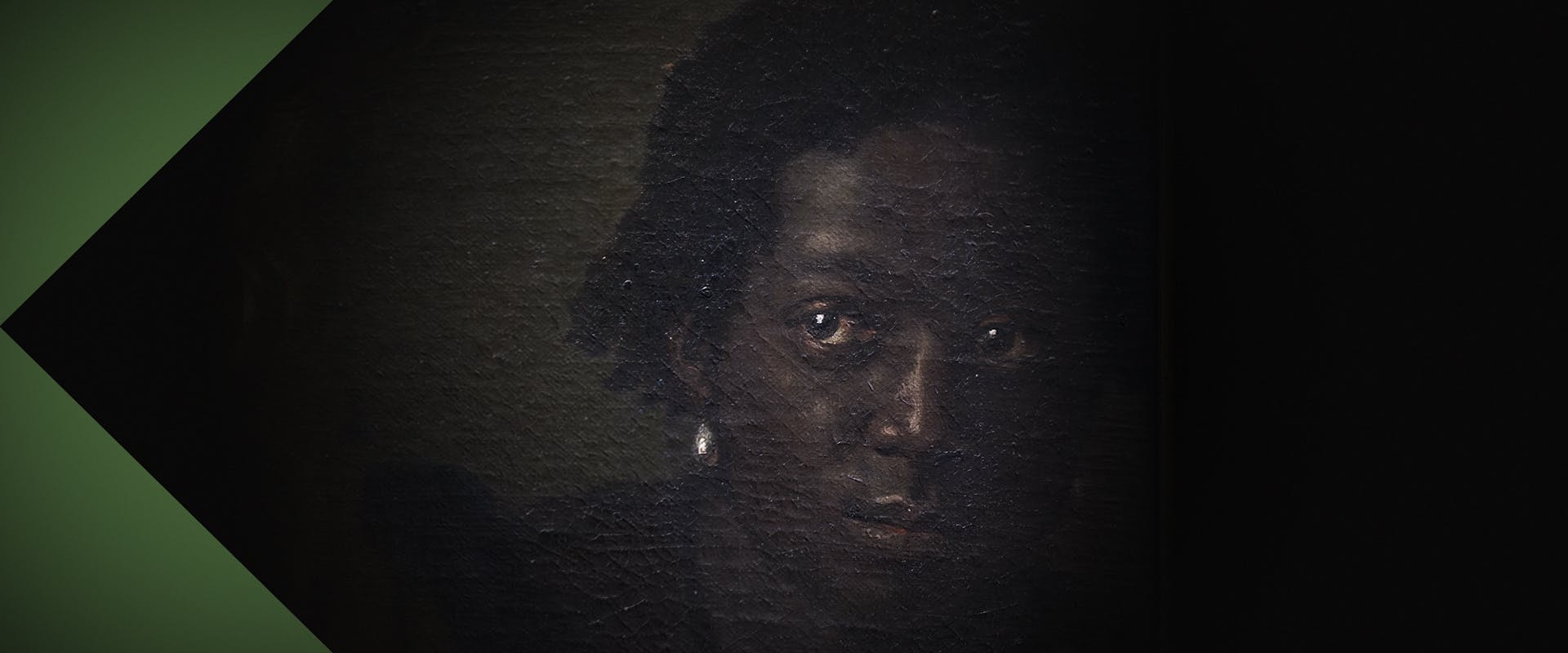

Bathed in light, Benedetto Silva appears in the Italian cultural archive as a ghostly apparition; a presence reminding us of something past, which we were not expecting.

In Domenico Tempesti’s half-length portrait, Silva seems to rise from golden fabric surrounding his shoulders. Wearing a silver dress coat and a white cravat, he stares piercingly out at the viewer with a faint smile; a young man daring to assert his presence, in space and time. Daring to look back regardless of the conditions surrounding his mysterious life in Italy. Serene and beautiful, once you are held in his line of sight, it is difficult to look away.

Sharply contrasted for dramatic effect, against a dark background, Benedetto Silva is represented in a limited palette of colours: gold, pink, silver, yellow and white. These are didactic colours that express what the artist could see, but also all the stories told and heard about albinism. Phenomenal stories from Africa, from the Caribbean, in the natural history books of Europe; about the moon, the supernatural, grey eyes, white lashes and eyebrows. Paleness, blindness, aloneness. Sensitivity. Pink skin that blushed when touched with pressure. And Yellow.

Yellow, the shadow of pigment lost.

Yellow, the colour of sunlight and inspiration.

Yellow as the weathered metaphor for so many ambiguous states of being (jaundice, and feverishness for example).

Golden yellow for gilding the lives of the noble and prosperous.

Naples yellow paint for Silva’s tightly curled Afro hair.

From birth in Angola to his position as an exotic page in the court of Cosimo III, we are left to imagine the life Silva experienced in Italy, since few documents survive. What was is like to be a human “rarity” in such an extravagant world? How did he navigate the city? Was he near-sighted, or farsighted? Why was he painted twice? Where did these paintings hang when they were completed? And was he asked for permission? The portrait is an intriguing mnemonic device for recording and materialising impressions (of treasured people), but there is, also, so much silence.

- 18/19Benedetto Silva

Another artist, Antonio Franchi, painted Silva when he was younger, but took a more conventional approach to representing difference. Namely, by exposing Silva’s body as an exotic specimen: outside in “nature”, half naked, draped in striped cloth, and holding a feathered arrow inscribed with text explaining his African origins. This kind of image was a common performance of race, although it is curious that he was painted in half length. Similar portraits made in other contexts represented people with albinism and piebaldism, in full body. Like Amelia Newsham, George Alexander Gratton, and John Bobey in England; also, Mary Sabina, Siriaco from Brazil, Adelaide from Guadeloupe, and Genevieve from Dominica.

Both paintings of Silva challenge us to reconsider our viewing positions in the present, looking at a subject whose own vision may have been compromised as he took his place in front of each artist. Face to face with Silva we experience the ancient lure of a curiosity, the human urge to stop and stare at the “Yellow Man” just like the Florentines of the 18th century. But the power in these portrait encounters, is in the looking back of the subject. For it is us that are caught inside Silva’s gaze.

text | Temi Odumosu

- 19/19Notes

Emily Wilbourne | Anton Domenico Gabbiani, Portrait of four servants of the Medici court

[1] I. Hugford, Vita di Anton Domenico Gabbiani (Firenze, 1762), p.10.

[2] A. Bernadette, Elizabeth I and Persian Exchanges, in The Foreign Relations of Elizabeth I, ed. by C. Beem, New York 2011, p.184.

[3] M. Charini, in Curiosità di una reggia. Vicende della guardaroba di Palazzo Pitti, exhibition catalogue (Firenze, Palazzo Pitti, gennaio-settembre 1979), ed. by K. Aschengreen Piacenti and S. Pinto, Firenze, 1979, p.59, n.27.

[4] I-Fd, reg. 65, fg. 214, see also ACAF (Archivio della Curia Arcivescovile di Firenze), Pia Casa vol. II, insert 119.

[5] M. Miller, Slaves to Fashion: Black Dandyism and the Styling of Black Diasporic Identity, Durham 2009, p.39.

[6] For Ali’s age see his baptismal details at I-Fd, reg. 58, fol. 22. Ali took the baptismal name Cosimo Maria Medici.

[7] ASF (Archivio di Stato di Firenze), Camera del Granduca f.35, 77r.

[8] ASF (Archivio di Stato di Firenze), Mediceo del Principato, f.6424, c.n.n.

Bibliographic References

John K. Brackett | Portrait of Alessandro de’ Medici by Vasari in conversation with his Portrait by Bronzino

T. F. Earle, K. J. P. Lowe, Black Africans in Renaissance Europe, Cambridge 2010.

Elizabeth Rodini | Cristofano dell’Altissimo, Portrait of Alchitrof

D. Bindman, H. L. Gates, Jr., The Image of the Black in Western Art, Cambridge 2010.

L. S. Klinger, The Portrait Collection of Paolo Giovio, Princeton 1990.

J. Spicer, Revealing the African Presence in Renaissance Europe, Baltimore 2012.

B. Wilson, The World in Venice: Print, the City, and Early Modern Identity, Toronto, 2005.

Bruce Edelstein | Justus Suttermans, Madonna Domenica delle Cascine, la Cecca di Pratolino e Piero moro

S. Bruno, Madonna Domenica delle Cascine, la Cecca di Pratolino e Piero moro, in Buffoni, villani e giocatori alla corte dei Medici, exhibition catalogue (Florence, Gallerie degli Uffizi, Palazzo Pitti, Andito degli Angiolini and Museo del Giardino di Boboli, 19 May-11 September 2016), ed. by. A. Bisceglia, M. Ceriana and S. Mammana, Livorno 2016, pp. 136-137, cat. no. 25.

S. Butters, Pressed Labor and Pratolino: Social Imagery and Social Reality at a Medici Garden, in Villas and Gardens in Early Modern Italy and France, ed. by Mirka Beneš and Dianne Harris, Cambridge 2001, pp. 61-87.

M. Chiarini, An Unusual Subject by Justus Sustermans, in “The Burlington Magazine”, CXIX, 886 (January 1977), pp. 40-41.

M. Chiarini, Domenica delle Cascine, la Cecca di Praolino e il Moro, in Sustermans. Sessant’anni alla corte dei Medici, exhibition catalogue (Florence, Palazzo Pitti, Galleria Palatina, Sala delle Nicchie, July-October 1983), ed. by M. Chiarini and C. Pizzorusso, Firenze 1983, p. 54, cat. no. 30.

L. Goldenberg Stoppato, Madonna Domenica delle Cascine, la Cecca di Pratolino e Pietro moro, in Un granduca e il suo ritrattista. Cosimo III de’ Medici e la “stanza de’ quadri” di Giusto Suttermans, exhibition catalogue (Florence, Palazzo Pitti, Galleria Palatina, Sala Bianca, 16 June-22 Oct. 2006), Livorno 2006, pp. 48-49, cat. no. 13.

P. Kaplan, Visual Sources of the ‘Blackamoor’ Statue, in ReSignifications: European Blackamoors, Africana Readings, exhibition catalogue (Florence, Villa La Pietra, Museo Bardini, Fondazione Biagiotti Cigna, May-August 2015), ed. by Awam Ampka, Roma 2016, pp. 49-59.

B. Meijer, Justus Sustermans at Palazzo Pitti, in “The Burlington Magazine”, CXXV, 969 (Dec. 1983), pp. 785-786.

Temi Odumosu | Yellow

C. V. Carnegie, The Dundus and the Nation, in Cultural Anthropology, 11 (4), 1996, pp. 470-509.

C. D. Martin, The White African American Body: A Cultural and Literary Exploration, New Brunswick 2002.

M. Pastoureau, Yellow: The History of a Color, Princeton 2019.

L. Thomas, Turning White: A Memoir of Change, Troy 2007.

On Being Present - vol. I

The hiperVision is part of the Black History Month Florence program

www.blackhistorymonthflorence.com

The project has been carried out and curated by Justin Randolph Thompson, in collaboration with the Department of Digital Strategies and the Department of Cultural Mediation and Accessibility of the Uffizi Galleries

Scientific coordination at Uffizi Galleries: Francesca Sborgi, Anna Soffici, with the collaboration of Chiara Toti.

Texts by: John K. Brackett, Bruce Edelstein, Dennis Geronimus, Ingrid Greenfield, Kate Lowe, Paul Kaplan, Temi Odumosu, Elizabeth Rodini, Emily Wilbourne.

Web editing: Andrea Biotti, Department of Digital Strategies, Uffizi Galleries

Editing: Patrizia Naldini, Department of Digital Strategies, Uffizi Galleries

Graphics: Jacopo Mazzoni, Black History Month Florence

Translations: Eurotrad snc.

Photos Francesco del Vecchio e Roberto Palermo

The image of the painting Portrait of Duke Alessandro by Antonio Franchi is published with the permission of Ministero per i beni e le attività culturali e per il turismo - Polo Museale della Toscana - Firenze

Published 20 Febraury 2020

Visit On being present - vol. II

Please note: each image in this virtual tour may be enlarged for more detailed viewing.